According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), transportation sources emitted 29 percent of all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the U.S. in 2007 and have been the fastest-growing source of GHG emissions in the country since 1990. Heavy-duty vehicles are the fastest-growing contributors to GHG emissions, the EPA adds, with Class 7 and 8 combination tractors and their engines accounting for roughly two-thirds of total GHG emissions and fuel consumption from the heavy-duty sector.

The EPA rang in the new millennium with an event horizon for diesel engine emissions and mandated that, effective with the 2007 model year, exhaust emissions spewing from on-highway truck engines be reduced by more than 90 percent.

Also beginning with the 2007 model year, all on-road diesel heavy-duty engines were required to be outfitted with a diesel particulate filter and another 50 percent of engines required nitrogen oxide (NOx) exhaust control technology.

By the 2010 model year, all on-road heavy-duty diesel engines were required to have NOx exhaust control technology.

The beginning of an era

Commonly referred to as EPA 2010, these new government emission standards focused on reducing pollutants, NOx and particulate matter (PM) coming from heavy truck engines to .2 gram per brake horsepower hour for NOx and .01 for PM.

Dr. Steve Golden, chief technology officer for Clean Diesel Technologies, Inc., says EPA 2010 – regardless of what engine makers did to the engine itself to get within compliance – forced the use of Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR).

“Once you got to 2010, everyone had to have every single catalyst component you could possibly think of,” he says. “Now you see these incredibly complex systems in terms of emission control to do a very high NOx conversion and a very high emission conversion in the same system.”

“[2010] kind of marked the era of SCR,” adds Mario Sanchez-Lara, Cummins’ director of on-highway marketing communications. “Really, 2010 was the time when all the after treatment that we needed was finally added to the engine system.”

Sanchez-Lara says EPA 2010 also helped Cummins to more intently focus its attention on SCR solutions, which had begun to emerge as the most cost-effective and fuel-efficient emission control technology.

“SCR brought with it some fuel economy gains, as we were able to not have to work on the NOx control within the engine and we were able to dial back the [exhaust gas recirculation] (EGR),” he says, “and that really helped us.”

At the time, the EPA estimated “that the proposed standards will add about $1,200 to $1,900 per new vehicle, but Golden says it was likely significantly more, not including additional maintenance.

“Just looking at all the components, I’d say it’s about $10,000,” he says, “if you take all the controls, not just the catalyst components.”

It ain’t easy being green

When 2010 finally arrived, and engine OEMs had cleared most of the early Phase I emission hurdles, the EPA teamed up with the Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) to introduce 2014 Green House Gas (GHG14) carbon dioxide (CO2) restrictions.

“[GHG regulation] is not only good for the environment, but it also brings gains in efficiency in the form of savings in fuel,” Sanchez-Lara says.

“Given that CO2 formation is directly related to fuel consumption, the current GHG regulations essentially mandate fuel economy improvements,” adds Kary Schaefer, general manager, marketing & strategy, Daimler Trucks North America (DTNA).

With viable, successful and emissions -complaint engines already on the market, GHG14 allowed engine makers to further improve emerging efficiencies.

“We put a lot of work into optimizing the combustion recipe to take advantage of the after treatment,” Sanchez-Lara adds.

GHG14 ratchets up next year with GHG17, with the end result requiring a nine to 23 percent reduction in emissions and fuel consumption from affected tractors over 2010 baselines.

Schaefer says DTNA used its GHG17 project as an opportunity to showcase full vehicle and powertrain development that meet the stringent regulations and provide real world benefits to its customers.

“We focused on powertrain, aerodynamics, controls and energy management, and more,” she says. “Detroit made innovations to reduce both parasitic load and friction, contributing to improved performance and efficiency. In addition, Detroit made improvements in fuel management and exhaust after treatment technology that also contribute to improved fuel economy.”

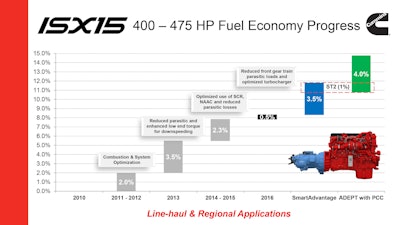

Sanchez-Lara says Cummins used GHG mandates to further refine the technologies that originally helped meet EPA 2010 compliance.

“We focused on reducing all the parasitic losses that we knew of and also modifying the performance curve of the engine to enable downspeeding,” he says. “We worked on making the engine breathe easier, to lose less power on some of the systems inherent to the engine, and developing an engine that produced peak torque as low as 1,000 RPM.”

As EPA’s Phase I neared its end, and engineers were still on task squeezing the final drops of efficiency from the truck’s power plant, OEMs began to hone in on the benefits of marrying the engine to other optimized systems on the truck.

“What has helped us is also the collaboration that is happening now with the power train,” Sanchez-Lara says, making note of Cummins’ partnership with Eaton on the SmartAdvantage platform.

“The collaboration between the engine and transmission, the proper gearing, is helping us to maintain the engine operating, most of the time, very efficient,” he adds. “That is helping to further the efficiency gains that the customers are seeing in miles per gallon improvement.”

Schaefer adds being able to leverage the expertise of Daimler’s global powertrain engineering organization has allowed Detroit to focus its efforts on integrating the individual powertrain components into an efficient package for its customers.

“In addition to engines and transmissions, Detroit has continued to expand its product offerings to include axles, safety systems and telematics,” she says.

While the EPA has forced the investment of billions of dollars into the development and design of today’s clean diesel engines, Sanchez-Lara said it is likely OEMs would have found their own way eventually.

“The customers’ economic pressure has always been there even if the greenhouse rule was not there,” he says. “I think our customers would have continued to ask us for lower operating cost and we would have ended up doing some of the things we did anyway. I think the rule helped, but I wouldn’t say it was the only reason to motivate us to bring the efficiencies we have delivered.”