Note: This is the first part of a three-part series that will examine the trucking industry’s driver shortage and the impact it is having and will have on fleets, shippers, drivers, rates, capacity and the industry as a whole.

Carriers are becoming increasingly anxious about finding good drivers. Good drivers want to know why, in a time of shortage, they are not being rewarded better. And shippers are keeping their fingers crossed, hoping trucks will continue to be readily available – and affordable.

The solution seems simple enough: boost driver pay.

But pesky basics like market economics and sound business practices keep getting in the way. Mix in some increasingly costly regulations that take drivers out of the industry with one rule and reduce productivity with another, and trucking faces a challenging operating environment – again.

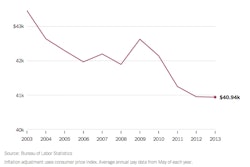

Though pay in some trucking niches has surged, it has been comparatively flat for trucking as a whole. Since 2003, wages for the entire for-hire trucking industry have grown 32 percent, slightly less than the entire private work force, at 34 percent.

The factors contributing to a persistent shortage of truck drivers are simple enough:

- A large number of long-time drivers are approaching retirement age;

- New regulations, notably the Compliance Safety Accountability program, have pushed many drivers out of the industry;

- Productivity losses due to the new hours-of-service regulations will increase driver demand, and;

- Fleets are reluctant to add capacity in a sporadic economic recovery.

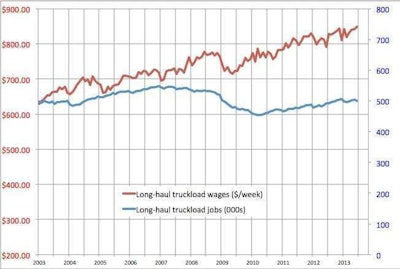

JOBS FLAT, WAGE GROWTH MODEST: The number of jobs in long-haul trucking has been basically flat for the past decade, though the industry logged substantial losses during the recession. Since its December 2006 peak, truckload employment has dropped 8.6 percent. Wages rose by a third over the decade, slightly lagging private-sector wage growth but well below historical wage growth during an economic recovery.

JOBS FLAT, WAGE GROWTH MODEST: The number of jobs in long-haul trucking has been basically flat for the past decade, though the industry logged substantial losses during the recession. Since its December 2006 peak, truckload employment has dropped 8.6 percent. Wages rose by a third over the decade, slightly lagging private-sector wage growth but well below historical wage growth during an economic recovery.These are some reasons why any coming capacity shortage will be different than the one a decade ago, which was brought on largely by the demands of a thriving economy, with some “regulatory drag” chipping away at truck supply. This time around, the imbalance is largely a matter of supply, and a capacity crisis is just an economic uptick away, suggests economist Noël Perry, managing director and senior consultant at FTR Consulting Group.

“The big puzzle in the last few years is why driver wages haven’t already gone up more,” Perry says, noting that rates and wages were making double-digit leaps each quarter during the previous recovery.

One possible explanation is that the wage data does not count extra payments such as hiring bonuses and increases in assessorial charges, Perry says.

Indeed, nearly half of carriers are offering sign-on bonuses compared to only 12 percent two years ago, consultant Gordon Klemp told trucking fleet executives during the 2013 CCJ Spring Symposium. Bonuses range from $250 to $5,000 for solo drivers and from $2,000 to as much as $15,000 for teams, says Klemp, principal with the National Transportation Institute.

“Recruiters say bonuses are here for the foreseeable future,” Klemp says.

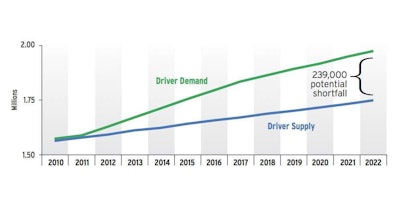

A GROWING SHORTAGE: The American Trucking Associations, assuming a current shortage of more than 20,000 truck drivers compared to available jobs, projects the gap to grow annually over the next 10 years.

A GROWING SHORTAGE: The American Trucking Associations, assuming a current shortage of more than 20,000 truck drivers compared to available jobs, projects the gap to grow annually over the next 10 years.Nevertheless, considering the demand for labor, Perry offers another possibility: “The fleets have been underpaying the drivers. If this hits the fan in the next year, the industry will have to radically change its behavior.”

On the other side of the equation, improved productivity means carriers are working harder – and smarter – to meet an increasing demand with the same resources.

“Drivers are getting a lot of miles, so their W-2s are going up even though their per-mile wage is not,” Perry says. “That’s keeping them happy.”

Perry also credits supply chain improvements for the productivity gains: More carriers are taking advantage of technology designed to optimize schedules and routing, and shippers have made their freight more attractive to carriers.

Shippers prepare

To assess carriers’ claims of a driver shortage, shippers simply need to “to look at your own service record,” suggested trucking analyst Thom Albrecht, managing director at BB&T Capital Markets.

“When you start to see a decay in either on-time pickup or on-time delivery, there’s probably a reaction up the chain, and it’s probably tied to drivers,” Albrecht said, addressing the annual Transplace Shipper Symposium in May. “When those begin to deteriorate, it’s either someone having problems with drivers, or your fleets are starting to play poker with you, and they may not be honoring their commitments.”

Albrecht pointed out that a driver gets 660 minutes of time behind the wheel in the daily duty cycle.

“The challenge for your organization is how can you help carriers find 20 or 30 more minutes a day?” Albrecht said. “A carrier can work smarter, but are you working with them to help them accomplish their goals? They can’t do it as a solo effort. As an organization, you’ve got to get across to your people to treat drivers with respect.”

Albrecht then posed the billion-dollar question: Is there another 2004 out there?

“By most accounts, 2004-2005 was nirvana for trucking companies and the ultimate migraine for shippers,” Albrecht said.

But Albrecht reads the data differently than Perry does, suggesting that supply, not demand, was at the root of the imbalance a decade ago. He noted three years of carrier bankruptcies, on top of substantial hours-of-service changes. “But the actual trend underneath was that loads were shrinking,” he said.

A recurrence of a situation similar to 2004 is possible in 2014, but not likely, because most of those underlying factors currently are not present, Albrecht explained. Specifically, carrier failures have been down, housing has been slow, and taxes are up.

More importantly, carriers have been signaling a cyclical upswing, and shippers are prepping for when truck capacity becomes extremely tight: alternatives such as shifting more freight to intermodal or dedicated fleets, expanding the core carrier base and using more brokered loads and third-party logistics services.

“I’m not convinced it’s going to be as tight as ’04, but it is going to be tighter than what we’ve seen the last couple of years because of hours of service – that’s the one commonality with 2004,” Albrecht said.

Perry, however, says to flip a coin. “The industry is operating at an historical level of efficiency. The margin for error is the smallest it’s been in an upturn. That’s the worry.”

As hours-of-service changes affect capacity, Perry predicts a 3 to 5 percent decrease in productivity due to hours of service, and that means carriers need 3 to 5 percent more drivers.

“Which is neither here nor there if the industry is incapable of recruiting that many,” Perry says. “We know, historically, that it takes time to do that. It is theoretically possible that we’re just going to run out of people to drive trucks, but that’s never happened.”

Indeed, without a “capacity buffer,” any boost in demand or regulatory reduction in capacity will throw the market into “a really critical situation,” including sporadic supply chain failures, the economist suggests.

His projected truck shortage, at 200,000, is a relative measure based on supply-and-demand equilibrium, Perry says. That means there might not be enough freight to support all those trucks, but shippers have to work harder to ensure capacity is available. At some point, shortages – and delays – will emerge at a high cost to the shipper.

So when will rates rise enough to support higher driver pay?

“If the regulatory drag is true, there will be a change in rate pressure,” says Perry. “Our numbers at FTR show convincingly that capacity is tight. And maybe the industry has been crying wolf about hours of service, but I don’t think so. I would put the probability at 40 to 50 percent that there will be a crisis.”

Albrecht hedged as well, saying that current bid agreements likely will be honored into the second half of this year, “but as we move into 2014, all bets maybe off.”