Managing the Moving Parts

With freight demand for 2012 unclear, carriers’ financial fates may rest on how they handle recruiting, rates and costs.

Gone are the days – if they truly ever existed – when a trucking company’s success or failure rested solely on overall freight volume. The philosophy that a rising tide lifts all boats might have worked in a less complex era, but not now.

But size isn’t the key variable distinguishing the “haves” from the “have-nots.” The carriers that will do well in 2012 are those with balance sheet strength, sophisticated driver recruiting and retention programs, strong shipper relationships and younger fleets, Larkin says. It’s just difficult for small carriers to achieve all of those competitive strengths, he says. But if a rebound in freight is stronger than anticipated, carriers that lack these advantages still could prosper – provided they price their services well, which is hardly a given, he says.

For Tom Wengerd, president of Berlin Transportation, a small regional carrier based in Millersburg, Ohio, there are plenty of opportunities even for small carriers that are prepared for the challenges. “Hiring and retaining qualified drivers and independent contractors will determine a carrier’s level of success in the next year,” says Wengerd. “We will look for clients that will help improve our drivers’ quality of life with better rates, improved loading hours and strategic lanes that will result in more home time for our drivers.”

As usual, carriers’ fortunes will rest more on how they play the hand they are dealt than on the hand itself.

The big picture

Given that few analysts anticipate that freight demand will surge in the coming year – even in the best case – the condition of the overall economy might seem somewhat less important than usual in shaping the fortunes of the trucking industry. Don’t be fooled; the economy remains a critical consideration.

“I think the economy is kind of the wild card,” says Larkin. In 2011, everyone’s expectations seemed out of sync with reality, he says. People were optimistic for the first half, which wasn’t very good. “More recently, the economy is doing better than what everyone thought, but everyone is bearish.” The United States has seen 1.5 to 2 percent GDP growth despite all the shocks – Europe, high energy prices, fears of a slowing Asia and riots in the Middle East.

“The big thing is the economy,” says Eric Starks, president of transportation forecasting firm FTR Associates. “If the economy doesn’t behave, nothing else falls into place.” FTR anticipates Gross Domestic Product growth of 2.4 percent – about half of what normally would be desired in a recovery. But much of the lagging growth is in the service sector, which is of less concern to trucking, Starks notes. So the 2.4 percent GDP growth translates into an FTR forecast of 2.6 percent growth in freight in 2012.

There is some potential for higher GDP growth if the recent bump in housing construction continues, but most of the risks are on the downside, Starks says. The big issue is Europe, he says, adding that it appears the European debt crisis will be contained. “A lot of indicators we’re looking at suggest that we averted a recession.”

Starks is not alone in predicting a close call.

“I still think that the U.S. economy will skirt by another recession,” says Bob Costello, chief economist for the American Trucking Associations. He believes that the U.S. economy will still grow, but at a slow pace. “Recession risk is still high because of eurozone problems.” The worst-case scenario is that the Euro collapses, leading to financial collapse in Europe to which there is U.S. bank exposure and a subsequent credit crunch here. “Any sort of major thing like this would lead to a recession.”

But this nightmare scenario wouldn’t seem that bad given the already weak U.S. economy, Costello says. “Even if there is a recession, it will be like falling off a curb, not a cliff.”

The political environment also remains a big cloud, although two threats could be resolved by the time you read this. One is the extension of the 2 percent payroll tax holiday. Another is extension of unemployment benefits. If those aren’t extended, that takes 1 percent off of GDP, says Costello. In both those cases, government action won’t stimulate the economy, but government inaction could stifle it.

Employment is another big factor. “The fastest way to improve GDP is to get people back to work,” notes Donald Broughton, transportation analyst for Avondale Partners. A 1 percent drop in the unemployment rate is worth a 2 percent growth in GDP, he says.

Costello expects the U.S. economy to generate about 96,000 jobs a month on average in 2012 – positive, but not enough to move the unemployment rate much. He cautions, however, not to focus too much on the unemployment rate because it is more important for trucking that the economy adds jobs.

There is at least a mild upside to slow job growth, Costello argues. “Corporate America has a lot of money, which is being spent on capital rather than labor.” He thinks businesses will continue this practice in 2012, and that translates into higher industrial production, which is good for trucking. (See “Building a recovery,” page 53.)

Not enough capacity

Analysts can debate the strength of the overall economy or all the inputs that go into defining freight volume, but all seem to agree that barring a double-dip recession in 2012, demand probably will outpace the supply of trucks and drivers. Trucking companies are adding a small amount of capacity, but it’s hard to find qualified drivers.

“The big issue is going to be capacity,” says Starks. FTR sees slight growth in capacity but projects that it will lag demand, translating into a 5 percent average increase in truckload base rates in 2012.

“We have had probably the most significant rightsizing we have ever seen in our industry,” Costello says. The result has been gains in average revenue per mile. Costello points to the flatbed segment, which lost the most capacity in percentage terms. Through September, flatbed loads are down 2.8 percent in 2011 compared to 2010. But average revenue per mile is up 7 percent.

Because of all the capacity coming out of the trucking industry, the current situation is essentially balance, says Larkin. “If the economy were to accelerate, then the supply-demand dynamic becomes wildly favorable to the trucker.”

In the monthly MarketPulse survey conducted by Randall-Reilly and CCJ, 57 percent of carriers say that driver availability is their top concern now, and two-thirds believe it will be their biggest challenge in 2012.

Driver quality – or lack thereof – due to the Compliance Safety Accountability program, the Pre-employment Screening Program and adoption of electronic logs is a big factor in trucking’s tight labor market, but it’s not the only one. Many carriers point to government policy. Although unemployment insurance might provide a welcome stream of cash into the economy, it can disrupt business in industries such as trucking where there are jobs available. “Until we stop the practice of paying people almost two years to sit at home on unemployment, this country will never fully recover,” says Keith Tuttle, president of Northwood, Ohio-based Motor Carrier Service Inc.

There also is a demand side to the driver availability challenge. Larkin points to the widespread application of electronic logs, which not only has exposed problems with driver quality but also has cost carriers productivity. Upcoming changes in the hours-of-service regulations could lead to further demand for trucks and drivers to offset lost productivity. And then there is hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,”which is siphoning off drivers, trucks and trailers. (See “A big fracking deal?”, page 18.)

Truck production is another capacity constraint. Even if carriers could hire enough drivers, several factors would slow the flow of additional trucks. The production capacity of truck makers is one constraint, especially due to shortages of parts and components. Tough credit markets also play a role, Larkin says. Fleets trading six- or seven-year-old trucks sometimes must trade three or four of them just to buy one new truck, he says.

“We are looking at just a bit above replacement demand levels,” Starks notes. “It wouldn’t take a whole lot more freight to create a capacity crunch.”

A caution on costs

In a typical year, freight rate increases in the high single digits would mean stronger trucking company profits. But 2012, like 2011 before it, might not be a typical year due to cost increases. Driver pay, equipment, tires and maintenance all are going up, and fuel prices remain unpredictable. And while they might not hit until late 2012, the costs in productivity that could be imposed by tighter hours-of-service regulations loom large.

Carriers’ costs soared in 2011 – by some 10 percent on average, according to FTR’s estimates. Starks thinks the growth will be half that in 2012, but that’s 5 percent growth on top of the 10 percent last year. “Fleets will be in an environment to push prices higher, but the question is whether they are willing to do it. If they didn’t do it in 2011, it’s hard to see how they do it in 2012.”

In the monthly Randall-Reilly MarketPulse survey, one-third of carriers said they expected the greatest 2012 cost increase in percentage terms to be driver pay. Other carriers split pretty much equally on fuel, driver recruiting, health care and tractors as the fastest-growing cost.

The challenge for carriers, notes Broughton, is that costs don’t determine pricing; demand and supply do. So somehow, carriers must offset those costs.

The solution in many cases will be figuring out how to get more desirable freight as opposed to rate increases, Starks said. In other words, carriers will seek out freight that involves lower costs and higher utilization.

Broughton, however, is less concerned about costs than he was a year ago. “Capacity is tight enough that carriers can get high single-digit price increases, and cost pressures will abate somewhat.” The cost pressures will be less on carriers that already have taken the asset utilization hit of electronic onboard recorders, Broughton says. He acknowledges that carriers likely will increase driver pay by about the same rate as freight rates, but he points out that driver pay is only 30 percent of a carrier’s costs.

Broughton also thinks the worst is over regarding costs related to equipment. For starters, carriers no longer are paying more for equipment that is less efficient, at least from a fuel economy standpoint.

Perhaps more important are financial considerations. “The used equipment market is strong and will be for a very long time,” Broughton says. So while depreciation costs will be higher, if carriers are going to get $15,000 more for their trucks, they won’t mind spending $15,000 more for the truck.

As for fuel, Broughton notes that the trucking industry steadily has gotten better at collecting fuel surcharges, so he is less concerned about a high diesel price. “It can put pressure on margins, but it doesn’t put pressure on margins the way it used to.”

Too much too little?

Despite the complaining, trucking executives usually acknowledge that a tight driver supply is necessary for financial health. Without it, carriers can’t get higher freight rates. But what happens if your inability to get drivers prevents you from enjoying the market potential?

“Demand is present from our current customer base, as well as add-on business,” says David Girault, chief financial officer of Pharr, Texas-based Royal Freight. “A lack of qualified drivers is inhibiting our growth potential, and this will only be exacerbated if the new hours-of-service regulations cut back driving time.”

In the latest MarketPulse survey, only 42 percent of carriers said they consistently were able to hire and retain enough drivers to haul all the freight available to them.

Carriers can survive without fixing driver recruiting and retention, but they should do better if they can address those challenges – especially if their competitors can’t.

Biggest Challenge in 2012?

1. driver availability 67%

2. freight pricing 9%

3. regulation 8%

4. political climate 5%

5. freight volume 3%

6. fuel costs 3%

7. other 4%

In the monthly MarketPulse survey conducted by Randall-Reilly and CCJ, 57 percent of carriers say that driver availability is their top concern now, and two-thirds believe it will be their biggest challenge in 2012.

Randall-Reilly MarketPulse Report, November 2011

Fast-rising costs expected in 2012?

Percentage of trucking executives who say item will rise the most in 2012 (in percentage terms)

1. driver pay 33%

2. fuel 15%

3. health care 15%

4. driver recruiting 14%

5. tractors 12%

6. tires 9%

7. truck parts 3%

In the monthly Randall-Reilly MarketPulse survey, one-third of carriers said they expect the greatest 2012 cost increase in percentage terms to be driver pay. Other carriers split pretty much equally on fuel, driver recruiting, health care and tractors.

Randall-Reilly MarketPulse Report, November 2011

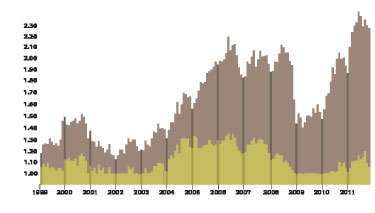

Cass freight index January 1990 = 100

The Cass Freight Index from Cass Information Systems shows expenditures on freight significantly outpacing shipments, a reflection of the pricing leverage carriers currently have due to tight capacity.

Cass Information Systems, Inc.

Building a recovery

Why is capital growth so strong? Part of the answer lies in pent-up demand, says Bob Costello, chief economist for the American Trucking Associations. Also, businesses are looking for certainty before they hire, and many still aren’t confident about the economic recovery. Since the third quarter of 2009, jobs are up only 2 percent, but capital expenditures are up 18 percent. “So it’s not a complete loss for the trucking industry.”

One reason trucking companies have noticed the tight capacity in trucking is that the manufacturing sector has been growing for nearly 2½ years – in large part due to capital expenditure growth. Manufacturing was up about 4.9 percent in 2011, but Costello believes that will slow to about 2.5 percent in 2012.

Even at a slower pace, manufacturing growth sets the stage for trucking doing better than the overall economy. “Retail is a very important part of the trucking industry, but we get more bang for the buck when something is domestically produced than an imported consumer good,” Costello says.

And manufacturing will continue to grow, says Donald Broughton, transportation analyst for Avondale Partners. “We and the Germans make better machine tools and parts than anyone else in the world,” he says. And the United States has the best software for industrial production, Broughton says.

Domestic assembly is rising – not just by American companies but foreign ones as well, Broughton adds, saying that a generally weak dollar in recent years has encouraged manufacturing in the United States by foreign firms.

Based on the expectations of supply chain professionals, manufacturing growth will continue in 2012. Expectations for 2012 are positive, as 69 percent of survey respondents expect revenues to be greater in 2012 than in 2011.

According to the semiannual forecast issued last month by the Institute for Supply Management, manufacturing revenues will rise 5.5 percent in 2012 over 2011. That’s on top of the 7 percent increase reported in 2011 over 2010. Virtually all of the manufacturing industries ISM tracks expect to see revenue improvement.

Manufacturing purchasing and supply executives “are optimistic about their overall business prospects for the first half of 2012 and are even more optimistic about the second half of 2012,” says Bradley Holcomb, chairman of the ISM Manufacturing Business Survey Committee.

Even with manufacturing strength, the economy can go only so far without higher consumer demand. “Retail consumption in general has been surprisingly good,” says John Larkin, transportation analyst for Stifel, Nicolaus and Co. But these days, trucking companies are less dependent on high levels of demand.

Larkin notes that inventories-to-sales ratios are very low, which will help carriers even if the economy softens. The lean inventories have resulted from a change in retailers’ philosophy, he says. While retailers traditionally wanted to keep shelves full even if it meant overstocking, many now would rather have stockouts but keep their margins in check.

Inventories-to-sales ratio: total business, seasonally adjusted

Lean inventories have resulted from a change in retailers’ philosophy; while retailers traditionally wanted to keep shelves full even if it meant overstocking, many now would rather have stockouts but keep margins in check. source: census bureau