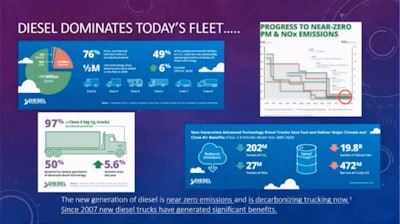

Allen Schaeffer, Executive Director at the Diesel Technology Forum, shared this slide as part of a recently staged debate among advocates, respectively, for diesel, battery-electric, and hydrogen-electric powertrains to dominate new truck sales in 2030.

Allen Schaeffer, Executive Director at the Diesel Technology Forum, shared this slide as part of a recently staged debate among advocates, respectively, for diesel, battery-electric, and hydrogen-electric powertrains to dominate new truck sales in 2030.

In the not-so-distant future world of 2030, what will power the plurality of new Class 8 trucks sold in the U.S.?

The answer, according to a Mobility Impact Partners debate held Wednesday last week, is definitely diesel, and nobody – not even advocates for battery and fuel cell technologies – made serious counter-arguments against that reality.

"Even with some of the direct policy interventions that have been taking place, in California particularly with their advanced clean truck rule, in 2035 only 40% of Class 8 tractors must be sold as zero-emissions vehicles," said Allen Schaeffer, Executive Director at the Diesel Technology Forum. "So that means 60% are still going to be diesel in California, which is leading the policy space here."

Schaeffer, the diesel advocate among three debaters assembled for the discussion, easily asserted in his opening statement that diesel powertrains are the most available and best performing among other technologies, that their increased efficiency over the last two decades has been equivalent to removing 43 million cars from the road, and that it's prohibitively expensive to create new infrastructure for new fuel types. The trucking industry, he said, thus simply demands more diesel trucks as time goes on.

All of this while diesel engines have reached "near zero" emissions on particulate matter and NOx, making them the clear choice for the future of freight, according to Schaeffer.

But while nobody effectively argued against diesel domination of trucking for now, the other debaters did make an extreme case for upsetting the status quo.

Diesel and the climate emergency

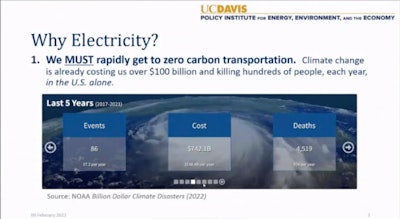

A slide from Colin Murphy of UC Davis, arguing the case for battery-electric powertrains in the debate.

A slide from Colin Murphy of UC Davis, arguing the case for battery-electric powertrains in the debate.

Colin Murphy, Deputy Director of the UC Davis Policy Institute, opened up his argument by admitting that battery vehicles alone won't transform the trucking industry, at least not by 2030.

"Obviously, a full portfolio of technologies will be needed" for the future of trucking, said Murphy. But while truck owners and buyers can pick and choose a path toward zero emissions, Murphy asserted that it absolutely must get there, and that getting there would mean the end of diesel.

"Climate change is no longer a future problem," he said, addressing the extreme weather disasters that scientists attribute to effect of greenhouse gases produced by human civilization. "Our choice is not do we pay money to go green or not, the choice is do we pay money to reduce carbon emissions or do we keep paying money to helicopter people off roofs and [rebuild] destroyed towns."

Murphy argued that "electricity has the best pathway to get to zero, and there's already hundreds of Class 7 and 8 trucks and real world data showing themselves to be successful." Even so, he acknowledged that most electric trucks at the moment work as pilot and demonstration platforms or in limited use cases, like the Tesla Semi transporting batteries to Tesla plants.

Electricity is generally cheap, he added, compared to diesel, and could produce lower cost-per-mile for trucking outfits. A recent study indicated that battery-electric vehicles come with lower maintenance costs that could push down total cost of ownership for their first owners across almost every duty cycle, given today's available subsidies. In the very near future, Murphy said, subsidies could shrink or become unnecessary.

Hydrogen to the rescue?

Murphy's main argument rested on the idea that switching to EVs would create difficulties, but that the battery-electric path presented the easiest, most manageable pathway to actual zero emissions as internal combustion engines have inherent inefficiences on a greater scale than electric motors, and that switching to hydrogen might not be plausible.

Yet Craig Scott, a group manager from Toyota, argued that hydrogen fuel cell technology, rather than solely battery-electric powertrains, could serve a wide cross section of applications, and that commonality with diesel, of a fashion, could be key to its long-term success.

He called fuel cells "very scalable" and spoke of growing "the demand for the molecule hydrogen, which therefore increases the growth in infrastructure, which therefore reduces the cost of hydrogen for everyone, creating a deeper pool of use cases for hydrogen, and round and round we go" on what he called the "hydrogen flywheel."

Scott knocked battery-electric vehicle talking points as part of an "echo chamber" that ignores the global scale of hydrogen adoption. "We didn't go from horses to gasoline overnight, and we're not going to go from diesel to hydrogen overnight either."

Besides holding out hope for mass adoption and government subsidies to push hydrogen prices below fossil fuel prices, Scott called attention to problems with state power grids, which in places like Texas and California have failed in the recent past with weather/fire extremity. Hydrogen, unlike electric vehicles, takes the pressure off electric grids and provides something that functions more like diesel fuel for mobile power generation.

"Hydrogen is the fuel that provides customers with something that looks just like diesel," said Scott. Like diesel, hydrogen production rests on driving down the price per volume, unlike electricity, which Scott pointed out can have variable and unpredictable costs.

After opening statements, the debaters were allowed to question each other on their presentations. While some of the questions veered into technical disputes on the findings of individual academic and industry studies, the debaters still traded barbs on the logical underpinnings of each others' arguments.

Scott pointed out that diesel trucks come with more vibrations and worse emissions, presenting workplace hazards to drivers who may soon be more inclined to drive less taxes electric or hydrogen vehicles.

Schaeffer noted that, even though every new deployment of an alternate fuel type usually gets a press release and headlines across the industry, the technologies are simply in their infancy and not close to ready to take on the burden currently shouldered by diesel. "The future will be more eclectic than electric," he believed. Schaeffer also mentioned the unseen envrionmental impact of electric vehicles, noting that battery production and recycling takes a toll on the environment likely excluded from most calculations.

In the end, too, efficiency in freight doesn't only mean fuel types. Schaeffer illustrated that by invoking the three or four local delivery trucks headed down his road every day. He suggested that better human resources and corporate partnerships could create a more sustainable freight future, which perhaps includes autonomous vehicles unlocking new fuel savings.