Fleet managers hoping to add battery-electric to their list of propulsion options in heavy-duty trucking applications are hampered by the technology’s added weight and range restrictions. New developments in battery chemistry and energy density are now inching the trucking industry closer to a viable long-haul solution.

When Our Next Energy (ONE) planted its roots in southeastern Michigan in 2020, company founder and CEO Mujeeb Ijaz set out to build a battery system for electric vehicles that could rival or exceed the performance of nickel cobalt manganese (NCM) batteries commonly found in many of today’s battery-electric passenger cars and light trucks. Three years and several battery iterations later, the company has now launched the Aries II battery platform. The new system is based on lithium iron phosphate (LFP) chemistry, which it says is a safer and more affordable alternative and nearly on par with the performance of NCM batteries.

Aries II specs include a 350-mile range with an energy density of 263 watt-hours per liter (Wh/L). Production is set to begin in 2024 at ONE’s new manufacturing facility outside Detroit. The Aries II follows the original Aries LFP battery architecture designed to deliver a 150-mile range for Class 3-6 trucks. The company has agreements with nine commercial vehicle OEMs, including Motiv Power Systems, Bollinger Motors and The Shyft Group.

The Aries II is the latest introduction in the evolution of ONE’s battery technology roadmap to address several battery limitations that the company hopes to overcome. Chief among those shortcomings is vehicle range. “A 300-mile electric vehicle is still not the level of performance needed in the real world,” said Ijaz, adding that the real-world range could be off by a factor of two compared to a 300-mile advertised range depending on vehicle speed and ambient weather conditions. At 80 mph in below-zero weather, he said a BEV’s advertised range is cut in half.

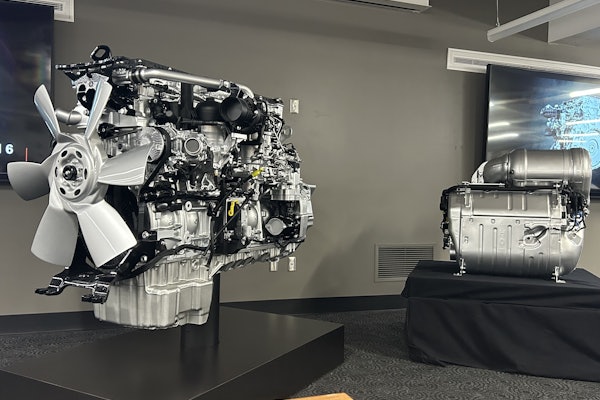

The Aries II platform from Our Next Energy uses lithium iron phosphate battery chemistry that the company says is safer and more sustainable than nickel-cobalt battery systems.

The Aries II platform from Our Next Energy uses lithium iron phosphate battery chemistry that the company says is safer and more sustainable than nickel-cobalt battery systems.

Safety is also a prime concern in development and production of battery-electric vehicles. Ijaz said LFP batteries lower the risk of a thermal runaway event, or battery fire. Oxygen, one of the ingredients needed for a thermal event, makes up 33 percent of nickel-cobalt battery chemistry. LFP uses phosphate instead of oxygen, reducing the chance for self-oxidation and resulting fire.

“If a cell had a problem, that would spread to the pack and then to the vehicle,” said Ijaz, citing a recent news story in India where a thermal runaway in a single NCM battery-electric vehicle at a charging location caused a chain reaction to 80 neighboring vehicles.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has issued six recalls in the last three years for thermal runaway events involving battery-electric vehicles. Ijaz hopes that mitigating this risk would help remove market resistance to battery-electric vehicle adoption at a larger scale. “We have to be cognizant that our decisions on safety technology and chemistry don't lead to something like an unintended consequence of public trust being lost.”

Material sourcing and abundance are also key advantages of LFP compared to NCM, Ijaz said, citing a doubling in price of nickel and cobalt in the last year alone. “In the context of the pandemic, the war in Ukraine and even the cobalt supply chain, that doubling isn’t a short-term problem.

“Based on all of this, we decided to make iron our root chemistry and see how we can progress our agenda on range,” he added. “If the cell is 400 Wh/L, how good does the pack design need to be to lift that above where nickel-cobalt is today?”

Battery tech for the long haul

ONE’s current focus is on improving battery technology for the passenger car and light truck markets, but battery evolution could eventually spill over into commercial vehicle applications.

From a Class 8 trucking perspective, Ijaz said battery electric technology requires a completely different approach than battery development for passenger cars. “Somewhere around one megawatt of energy on a Class 8 truck is beginning of that market,” he said. “LFP today can do about 400 to 500 kWh. There has to be a step, something big has to happen to get to that one megawatt.”

ONE’s forthcoming Gemini battery platform could become a conversation starter for battery-electric relevance in over-the-road trucking applications. Gemini's dual-chemistry architecture combines LFP and anode-free cell systems. ONE touts a 600-mile range by combining the performance of the Aries II with an auxiliary range extender battery pack that serves only to recharge the traction battery.

Gemini's dual-chemistry architecture combines LFP and anode-free cell systems for a range of up to 600 miles.

Gemini's dual-chemistry architecture combines LFP and anode-free cell systems for a range of up to 600 miles.

“We’ve talked to many Class 8 truck buyers, and the way they are thinking about the cost models, they think the durability of the Gemini is not enough but they have made some indications of what it might take,” said Ijaz.

Battery longevity presents a specific challenge for fleet managers. “To climb from 200 to 400 [charging] cycles is on our minds,” said Ijaz. “We are at 300 now. I think in a few years we can offer Gemini as an option to the Class 8 trucking with a durable product to enter the market.”

Based on ONE’s rate of development, Ijaz forecasts a five-year window for providing a durable, one-megawatt-plus battery product for the Class 8 market. “Then we have to work on cost models as well,” he added.