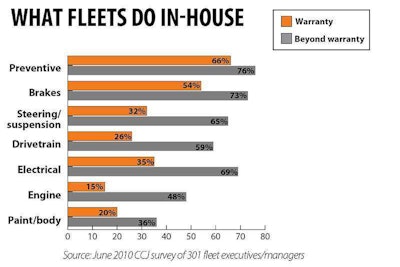

Cost control is an essential component of effective fleet management, and maintenance is one area where managers can make a dramatic impact on the bottom line. No doubt that’s one reason more than two-thirds of CCJ readers surveyed last month perform preventive maintenance in-house, and more than half conduct their own brake and tire maintenance. And that’s just during the warranty period. Once the vehicle is beyond warranty, half of fleet operations perform their own engine repairs, and the majority performs all other maintenance tasks except paint and body work.

And yet, the simple truth is that electronics have made vehicles more complex, and complexity is the biggest reason fleets outsource repairs. “If you’re a dealer for an OEM, you send your technicians to their schools,” says Wayne Demma, a sales representative with Volvo and Mack dealer Chicago Truck Sales and Service. “We see everything that comes out before everyone else sees it. Many times, the fleets don’t see new equipment or issues until after the equipment is purchased.” Fleets then have to wait for technician schools to offer training on the new equipment.

Aside from the training and experience, the cost of purchasing computer programs and diagnostic equipment necessary to maintain newer tractors makes outsourcing an attractive alternative for many fleets – particularly smaller ones. But regardless of a fleet’s philosophy on routine maintenance and repair, there’s one situation in which few fleets – especially over-the-road operations – can avoid working with outside providers: A breakdown. In any situation, the keys are communication, cost control and an understanding by providers that uptime is king.

Control and comfort

Does the ever-increasing complexity of trucks today – particularly engine systems – make in-house fleet maintenance a losing battle? Not according to Bobby Allen, director of maintenance for Danny Herman Trucking, a Mountain City, Tenn.-based fleet of 165 company trucks, 100 owner-operators and 750 trailers. Allen, who supervises about 35 technicians scattered among five repair shops across the country, says Danny Herman keeps maintenance in-house mainly to control costs.

“Our mechanics have a better understanding of the trucks and the issues we commonly face,” Allen says. “The guys are used to seeing the same type of trucks, the same type engine and the same type of equipment on the trucks.” That familiarity also makes it easier for Danny Herman to control parts inventory and labor.

“Doing repairs, maintenance and tire work in-house keeps our fleet availability at 99-plus percent,” says Mike Maher, fleet supervisor for Kansas City Power & Light Co. “No dealership or independent shop can provide service at this level, plus it is more cost-effective to do in-house – very few comebacks, etc. Our company has been in business since 1882, and we do have a good handle on our costs.”

Those sentiments are shared by Wayne Beaudry, vice president of fleet maintenance for Maywood, N.J.-based Metropolitan Trucking. The fleet’s major hub is in Bloomsburg, Pa., where it maintains 790 trailers and 318 tractors. “We prefer to keep things in-house because I can control the cost better and keep an eye on the quality of the work,” says Beaudry, who has noticed a marked uptick in prices for outsourced labor. “Because dealers aren’t getting large volumes of new truck sales, they’re trying to make up a lot of their profits in the shop,” he believes. “The parts markup is starting to get pretty high at a lot of places.”

On top of that, some dealerships and shops pay technicians on a parts-commission basis, which makes it virtually impossible for a fleet that outsources to control repair costs, Beaudry says. “I’ve had shops tell me they can’t do a simple repair – put a spring in a fifth wheel – for that reason,” he says. “They come to you instead and tell you they have to sell you a whole new fifth-wheel unit because their technicians are commission-based and they get a cut out of that new component as opposed to just replacing the spring.”

Opting for outsourcing

Few fleets perform everything in-house, and according to last month’s survey, a quarter of fleets use independent repair shops or dealers even for preventive maintenance. B&B Global Logistics, a Montreal-based dry box hauler with three tractors and five trailers, had been fortunate to benefit from the services of a nearby mechanic that owned his own shop until the recession forced him out of business. “He would do all of our maintenance and oil changes,” says Alex Bardos, B&B president. “He was a little more expensive than others, but he was thorough. That’s why we have a 1994 Peterbilt with 3 million kilometers still running to Florida every week.”

It’s a different story for vehicles at NOTS’ remote terminals across the country, where Sabo sends them out for repair work – even routine PM. “We don’t have shops at those locations,” he explains. “It’s not cost-effective for us to do that.” Over the years, Sabo has become close friends with several of the remote repair shop owners and will send a tractor to a dealership only if he has no other option.

Not surprisingly, the use of outside providers correlates significantly with warranty status, according to the June CCJ survey. For example, dealers get two-thirds of engine work within warranty but only 28 percent of engine work out of warranty. Similarly, dealer shops’ share of drivetrain work drops from about 57 percent during warranty to less than 20 percent afterward.

After the warranty period, most maintenance and repair comes in-house except for work that requires special training or tools, such as engine and paint/body work. But dealers lose little business to independent garages except with regard to paint/body work. It’s understandable that fleets would bring more work in-house after warranty, but why don’t they outsource more to garages than dealers?

For many fleets, a relationship with the dealer that sells the truck is the easiest to maintain, and the dealer’s experience with the equipment is important. “OEM technicians see all the problems, and they see them often,” Demma says. “They have information and a backlog of experience that the fleet techs often don’t. And they can repair a truck a lot faster because they’ve probably already seen four or five cases with that same problem.”

A related issue is training, which can become expensive and tough to schedule. Truck manufacturers typically hold dealer service departments accountable for training, and that’s good, says Charles “Chas” Voyles, service director for the Troy, Ill.-based location of Truck Centers Inc., a Freightliner and Western Star dealer with locations in the St. Louis area and southern and central Illinois.

“We train five days a week every week, and I can’t get enough guys in to satisfy my standards,” says Voyles, who also serves as chairman of the Technology & Maintenance Council’s Service Provider Committee. That level of training is expensive. This year, monthly training costs for the 37 technicians just at Truck Centers’ Troy location have averaged nearly $12,000.

Fast, dependable service?

What happens when service providers don’t train enough? One consequence is that a bottleneck can develop because certain jobs have to flow through certain technicians.

Wayne Beaudry, vice president of fleet maintenance for Maywood, N.J.-based Metropolitan Trucking, instructs a technician on parameter settings for a 2008 CARB-certified Detroit Diesel DD15 engine on a 2009 Freightliner Cascadia.

Wayne Beaudry, vice president of fleet maintenance for Maywood, N.J.-based Metropolitan Trucking, instructs a technician on parameter settings for a 2008 CARB-certified Detroit Diesel DD15 engine on a 2009 Freightliner Cascadia.“Right now we seem to be having a problem with all the new technology – even the dealers can’t seem to keep up with training techs to handle the problems,” says Kevin Tomlinson, director of maintenance for South Shore Transportation, a regional flatbed operation based in Sandusky, Ohio. “It seems like everyone has one guy that knows how to work on the certain thing, but that is it. So if you have three tractors in with a problem in that area, he is the only one that can work on it, which tends to keep my truck in the shop longer.”

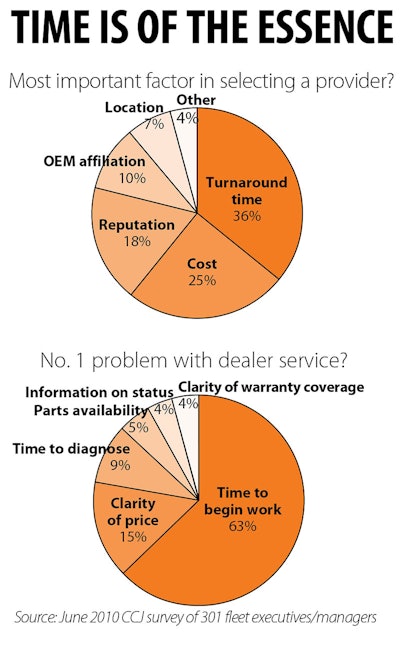

Aside from the expectation for quality work, which is a given, turnaround time is the most important factor in selecting a service provider – more important even than cost. But then, slow work truly is a cost for fleets.

“The biggest problem that I have with dealers is truck turnaround time,” says Steve Teeple, president of Pollywog Transport, a small refrigerated truckload carrier based in Palmetto, Fla. “To run an efficient fleet does not mean having trucks tied up in shops for weeks. As a small company with 35 trucks, we need to keep 34 on the road.”

NOTS’ Sabo believes dealership representatives often don’t take as much ownership in the service they provide. “Unfortunately, my attitude is that the small shops care more,” he says. “You’re usually dealing with the owners of the repair shops who understand it’s their money on the line as well.”

Sabo detects little urgency from larger dealerships when one of his vehicles lands in their yards. “They don’t understand how we’re affected by downtime,” he says. “They just don’t understand the consequences of that truck sitting there.”

It’s a sentiment Beaudry shares. “There are dealerships I can call on a Wednesday with a turbocharger that’s blown up,” he says. “I’ll ask them when they can get to it, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, next Monday.’ That’s worthless to me.”

After the independent shop Bardos was using went under, he took a new tractor to a dealership for warranty work and was left with a bad experience. The dealership spent eight weeks fixing the truck, including three weeks diagnosing the problem. In the meantime, Bardos still had to make payments on the truck. “I could’ve gone bankrupt dealing with this truck,” he swears.

When Bardos finally got the truck back, he discovered to his horror that it still wasn’t running right. The entire ordeal ended up costing him nearly three months of downtime and more than $2,500. “The worst problem is that it cost me three drivers, including my best driver, who’d been working with me since 1994,” he says. “I can’t blame him. He didn’t work for six or seven weeks. It was enough to sour anybody.”

Bobby Allen, director of maintenance for Danny Herman Trucking, says the Mountain City, Tenn.-based company keeps maintenance in-house mainly to control costs.

Bobby Allen, director of maintenance for Danny Herman Trucking, says the Mountain City, Tenn.-based company keeps maintenance in-house mainly to control costs.Demma agrees that dealers could do more to share a sense of urgency when trucks come into their repair bays. One problem he sees is that many dealers have priorities that are often at odds with those of a fleet – particularly a fleet that they don’t know as well as their older, more frequent customers. “The larger dealers do better in that regard, but many smaller dealers often don’t have the staffs they need to cover stray trucks that come in,” Demma says.

Also, many fleets that have arrangements for labor discounts may find themselves a lower priority in the shop. “Many dealers take the attitude that their bottom line comes first,” Demma says. “Why would they divert their resources on a discount to a fleet when they have bread-and-butter customers to take care of? That’s today’s business climate. It’s brutal.”

Beaudry knows there are many good dealerships out there. “You can go into their shops, and they’ll diagnose the problem within two hours and get you in the shop within a half a day,” he says. “When they do that, I don’t mind dealing with them. But you get some shops where you’re almost cringing at what they’re going to tell you.”

All about trust

Despite Bardos’ bad experiences with dealerships, he now prefers to take his 1994 Peterbilt to Paccar dealers when he’s on the road. “It’s an older truck, and I trust them a little bit more,” he says. “You pay a premium, but their service is exceptional, and they’ll fix it right away. And I’m willing to pay that premium because time is money and downtime kills you.”

– Avery Vise contributed to this article

TMC tackles conflicts over outside repairs

Committee to develop RPs for service providers

The old joke “Everyone complains about the weather but nobody does anything about it” basically sums up how fleet owners have dealt with dealers and garages for decades. The gripes are as old as trucking itself – the provider isn’t fast enough, it overcharges, it doesn’t handle warranty correctly, quality control is poor and so on.

Chas Voyles, chair of TMC’s Service Provider Committee, hopes his group can help change attitudes.

Chas Voyles, chair of TMC’s Service Provider Committee, hopes his group can help change attitudes.These issues often arise in formal and informal discussions at Technology & Maintenance Council meetings, so last year, TMC decided to do something about it. Spearheaded by then-TMC Chairman Brent Hilton of Little Rock, Ark.-based Maverick Transportation, TMC created the Service Provider Committee as a forum for bringing more dealers and garages into TMC to help establish a dialogue with fleets.

The committee’s membership includes both fleets and service providers. Chairing the group is Charles “Chas” Voyles, service director of the Troy, Ill.-based location of Truck Centers Inc., a Freightliner and Western Star dealer with five locations and two satellite parts facilities in St. Louis and southern and central Illinois. Voyles had known Hilton for many years and had considerable experience working in the maintenance departments of fleets large and small.

One of the biggest issues the Service Provider Committee is hoping to address is the frustration fleets feel about trucks not being able to get into a shop in a timely manner. “The problem might be as simple as a loose hose clamp, but the service provider wouldn’t look at it for a couple of days,” Voyles says. “Downtime is always the biggest issue, and there’s a feeling that dealers didn’t understand its importance.”

To address this chronic worry, the Service Provider Committee established a task force that is trying to develop a recommended practice (RP) on developing and implementing a rapid repair assessment program. Currently, the task force is assembling documentation from dealer and independent shops on current practices and hopes to go to ballot with an RP after the TMC annual meeting next year. Other Service Provider Committee task forces will address:

• Warranty handling;

• Repair order approval and authorization;

• Customer notification;

• Successful repair shop practices;

• Measuring customer satisfaction;

• Recommended standard repair times; and

• Quality control.

Perhaps the most controversial of those task forces is the one on standard repair times, but the task force only will identify sources for developing standard repair times; it won’t try to specify them.

Most of the task forces are intended to be collaborative efforts among TMC’s fleet and service provider members, but a few – such as successful repair shop practices and measuring customer satisfaction – are aimed primarily at service providers.

Perhaps most of all, Voyles hopes the Service Provider Committee can help change attitudes. “Service providers have to change the way we think when it comes to the customer. We need them. They don’t need us.” By that, Voyles means that fleets can choose other service providers or do the work themselves, but without trucks, dealer service departments and independent garages don’t have incomes.

“I get to have a job and feed my family because of what they do – truck drivers and fleets,” Voyles says. “We need to have an attitude of servitude. You would be surprised at the lack of that in the business.” – Avery Vise

Making service an open book

Some of the biggest frustrations and points of conflict between fleets and service providers relates to communication. On the front end, fleets and providers might play phone tag for hours to get work authorized, potentially losing valuable truck utilization that never can be recaptured. And once the repair is done, it’s not uncommon for fleet managers and service managers to argue over whether particular repairs had been approved.

One of the key features of MVAsist, a Volvo and Mack offering on the Decisiv platform, is to make the interaction between the truck owner and the service provider as transparent as possible to minimize miscommunication and disputes.

One of the key features of MVAsist, a Volvo and Mack offering on the Decisiv platform, is to make the interaction between the truck owner and the service provider as transparent as possible to minimize miscommunication and disputes.Andy Gomel won’t claim that those and other conflicts have vanished, but the situation for Hill Bros. Transportation – an Omaha, Neb.-based refrigerated truckload carrier that operates about 360 trucks – has improved greatly over a couple of years ago.

“If it doesn’t happen in Omaha, I take care of it,” says Gomel, Hill Bros.’ breakdown manager. In the past, Gomel found communications with the Volvo dealers he uses for over-the-road service to be inconsistent. “That was frustrating. It was hard to know what expectations I should have.” Often he had to deal with phone tags and slow response. “Sometimes a half day would go by, and nothing would get done.” Even more important than getting the job done was knowing when the job would be done. “If someone tells me that a truck would be done at 3 p.m., I relay that to operations. I can take bad news, but I want it to be accurate bad news.”

Much of Gomel’s frustration evaporated when Hill Bros. began using MVAsist, a management tool powered by Decisiv and offered through the Volvo and Mack dealer network. MVAsist pulls together in one interface all the communication among the parties to a service event.

“MVAsist has given us a fresh approach to communicating to service providers that is new to both the customer and ourselves,” Gomel says. If there’s a billing issue, for example, everyone can see the specifics of the original agreement. “The main thing it can do is add pressure on the dealers. It holds folks accountable in a way that a phone call doesn’t.”

– Avery Vise

CCJ Webinar:

Assessing Repairs More Quickly

Join CCJ and its sister publications Successful Dealer and Truck Parts & Service for a July 27 webinar on rapid repair assessment. Panelists include David Foster of Southeastern Freight Lines and Chas Voyles, chairman of the Technology & Maintenance Council’s Service Provider Committee. For more information, go to CCJWebinars.com. n