On Monday morning, Sept. 9, a truck driver was supposed to deliver a flatbed load of fencing material near the mouth of Butterfield Canyon on the southwest corner of the Salt Lake valley in Utah. The driver never came. Instead, around 1:00 P.M. the police received a call for help. The driver was stuck on a sharp left turn high in the canyon. The trailer tires were inches away from careening down a steep cliff at the center of the turn.

Why was the driver in the canyon? Was he trying to catch an aerial view of the biggest hole on earth, Utah’s world-famous Bingham Copper Mine? Apparently, according to this report by Utah’s KSL News, the driver was following his GPS navigation system. It told him to keep on going. The report didn’t specify what GPS device the driver was using, but something was terribly wrong with the route.

Perhaps the driver selected a spot on a map for his destination rather than a specific address? Or perhaps the address he entered wasn’t correct? Both scenarios are possible. The destination was an undeveloped parcel of land at the mouth of the canyon used by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) for its Wild Horse and Burro program.

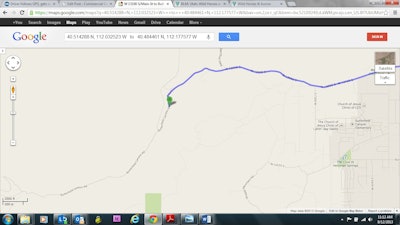

When entering the address of the BLM land into consumer navigation apps, the destination, labeled “B” on the map below, is on Butterfield Canyon Road. It’s easy to see the driver would have no place to turn around if he went too far.

One of the problems with GPS systems is that drivers can be put in precarious situations during the “final mile” of a route. Perhaps the destination is on a dead-end street or in an area where a driver cannot safely turn around should he or she miss their intended target. The accuracy of GPS is partly to blame, but bad data in general can be a nightmare for truckers. In this case, it nearly cost one his life.

Could a commercial truck routing and navigation system have prevented this from happening?

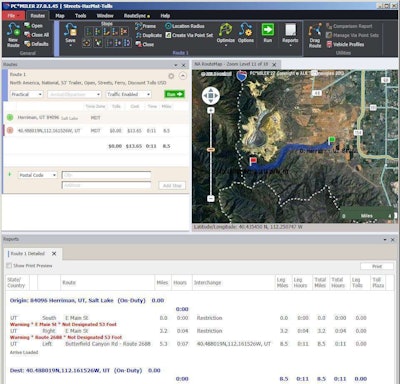

ALK Technologies ran the same route in its PC Miler mapping, mileage and routing software. Assuming the tandem-axle flatbed the driver had was 53 feet long, PC Miler–a system that dispatchers typically use in the office–would have issued a warning about the route: “Not Designated 53 Foot.”

ALK’s PC Miler, version 27, warns the route is not safe for a 53-foot trailer

ALK’s PC Miler, version 27, warns the route is not safe for a 53-foot trailerThe warning would have caused the dispatcher to question the movement and perhaps call the shipper for more specific directions about the delivery location. The driver should have also been told to not proceed up the canyon road, no matter what.

ALK also has a feature called RouteSync that marries a fleet’s custom route settings in PC Miler to its in-cab navigation application, CoPilot Truck. A dispatcher, for example, could use an “Avoid” feature in PC Miler for the Butterfield Canyon Road. If a driver were assigned to this delivery route, the CoPilot Truck navigation system would have given the driver a route that avoided the canyon road.

For an example of how a carrier is using the RouteSync functionality to perfection, read this CCJ article about Paul’s Hauling.

Telogis, which offers the Telogis Navigation (formerly NaviGo) system for commercial fleets, also ran the route for the purpose of this article. Rick Turek, vice president of navigation for Telogis, said most routing issues stem from bad data about the destination, which was certainly the case in this situation.

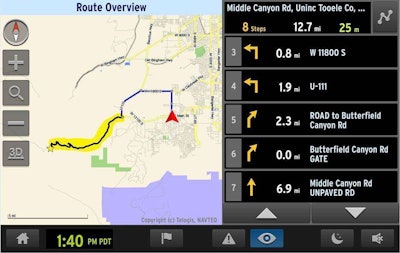

The Telogis Navigation system lets the driver preview the route in advance.

The Telogis Navigation system lets the driver preview the route in advance.Telogis Navigation has a built-in ability to fix bad data issues on the server side before sending the route to its in-cab navigation application.

In the office, a dispatcher also could have manually moved the delivery location to the correct place on the map and assigned a specific location where the driver should enter and depart. The dispatcher could also enter custom notes. When the driver approached the destination, the navigation system would read these notes to the driver, like “look off to the right for an open field.”

With hundreds of fleets and the more than 100,000 drivers in the Telogis community, the map and routing information it has is continuously updated by users themselves. Drivers, for instance, can provide feedback directly from their in-cab application, he says.

When a company assigns a driver to a load in the office, the vehicle’s location and scheduled stops are sent to Telogis Navigation servers. An optimal route is calculated and sent out to the cab. If the fleet and driver in this scenario were using Telogis Navigation, the driver would have seen a preview of the route in advance. The road with its narrow canyon switchbacks would have raised an immediate flag. But, the Butterfield Canyon Road is restricted on the server side, so the driver never would have received a route that put him on that road.

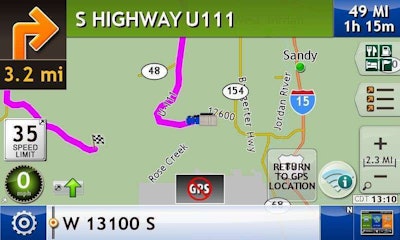

Rand McNally’s IntelliRoute TND application avoids the canyon road

Rand McNally’s IntelliRoute TND application avoids the canyon roadA driver that input the route on Rand McNally’s IntelliRoute TND (stands for Truck Navigation Device) would have correctly avoided routing on the road, as shown to the right. With the TND device, drivers can preview the route in advance and chose to avoid certain segments, which in this case wasn’t necessary since the route did not include the canyon road. When a driver avoids a segment is usually due to construction or personal preference.

Ultimately the driver is the captain of the ship, but as this instance proves, not having the right routing tools and good data nearly made this captain sink his ship in a mountainous grave.