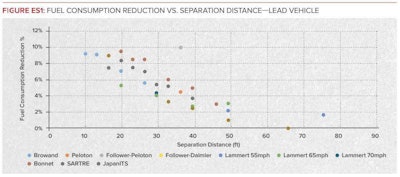

The potential fuel consumption savings versus an isolated single vehicle varies depending on the separation distance of the trucks, but the report says at a following distance of 40- to 50-feet platooning can lead to 4 percent average savings over the two trucks after accounting for traffic, terrain and time when equipped trucks will not be operating in a platoon.

“We see platooning being the next logical automation,” says Mike Roeth, executive director of NACFE. Roeth emphasized that while platooning uses select autonomous technologies, it’s being unfairly and incorrectly labeled as driverless tech. “Why are we even looking at autonomous trucks when we don’t even link up two 53 foot trailers?”

Following distances of 50-feet or less violates practically every safe standard on the road, but Rick Mihelic, NACFE program manager, says platooning can actually reduce the amount of time it takes to stop a truck by automating the process and removing the lag of time a driver would recognizing a braking event and physically being able to apply the brake.

“The reaction of the rear truck’s brakes within a millisecond or so is huge,” Roeth adds.

Platooning is the race car equivalent of drafting. In a platoon, once the trucks have moved into close following distances, all of the engaged vehicles receive a fuel economy boost thanks to increased aerodynamic efficiencies. The lead vehicle would dictate speed for the platoon, while the trail vehicle maintained a pre-determined speed.

The lead vehicle will bear the brunt of the aerodynamic load and will typically see marginal fuel economy boost. Trailing trucks in a platoon, which operate in a low air pressure aerodynamic “sweet spot,” can see significant increases in fuel economy performance at highway speeds.

Despite the technological sophistication needed to stitch together a platoon, Roeth says confidence level among fleet managers that platooning technology, as well as the concept of platooning and the projected fuel economy gains it can yield, is high across the board.

However, he adds there is a lag in the confidence that platooning can work in the “real world,” most notably in heavy traffic or mountainous terrain.

Despite the bulk of required technologies being currently available and purchased by many fleets, fleet managers are doubtful that drivers will be willing to engage in platooning operations. Roeth says fleets may have to incentivize platooning by building it into drivers’ fuel economy bonus plans.

“There will be early adoptions, including large mega fleets that operate within close proximity to each other,” he says, “as well as some small fleets that might have trucks in dedicated routes that could pair up.”

Additionally, fleet managers cite concerns about various safety issues and the security of the electronic systems used to connect and tether the vehicles together in a platoon.

Other concerns include cost, system reliability and questions about intra-fleet operations – notably how fuel credits will be accrued and shared.

“Now platooning can help pay for the accelerated adoption of these technologies that are being put on the truck,” Roeth says, adding its too early to pinpoint the cost of the componentry that enables platooning but payback is expected to come within two years.

“This is not something that you’ve got to go buy that [isn’t] already being bought to some degree,” he adds, noting the vehicle-to-vehicle communication technology needs the most work. “The security of that communication is critical.”

The communication part of the technology is still very new and standards are not well defined, adds Mihelic.

“We’re just going to have to see where it goes in the next several years,” he says.