Zero tailpipe emissions aside, one of the attractions to electric powertrains is a perceived reduced maintenance cost. The expectation is that electric trucks will require less maintenance since they feature fewer moving parts and require less fluid changes.

Clarity on just how much savings an electric truck can provide isn’t quite clear since there are so few of them on the road in a commercial setting and an inability to sell the maintenance benefits with hard data, Chris Nordh, director of advanced vehicle technology for Ryder System, Inc., says will likely slow adoption until those figures begin to firm up.

“I don’t think that it’s going to be the availability of the product and the technology. I think that’s coming along fairly quickly,” he says of slow-growth adoption. “I think it’s going to be the proving out of the maintenance costs. There’s a lot of predictions being made about the reduction of costs but nobody has the data yet.”

And even though costs will likely be reduced by a measurable degree, electric commercial trucks will still require repair and it will be a sophisticated process.

“Maintenance on the electric vehicle is still very important,” Nordh says. “It becomes a higher skilled labor but a lower number of hours needed to maintain the vehicle. When there is something that goes wrong with an electric vehicle, you have a very significant diagnosing exercise and you have to have really experienced technicians in order to do those diagnostics.”

Regardless of how often you have to service an electric vehicle, parts have to be available on demand and not every corner parts store has electric components sitting on the shelf.

“They’re not going to have inverters. They’re not going to have spare batteries when those fail,” Nordh says.

Upon inking a sales and service agreement with Chanje last year, Nordh says Ryder imported “several container loads of spare parts” for the vans, “and we now have those sitting in our distribution centers. We have overnight capabilities for all the parts that could be needed for those vehicles,” he says.

Maintenance savings are only bankable if you’re not blowing through your tire budget with electric torque. Elon Musk himself describes the performance of his electric Semi tractor in 0-to-60 times and lauds its racecar-like handling.

Upcoming Event

CCJ Symposium: Addressing the implications of electrics

Alternative powertrains are not new to trucking, but few have held the promise to permeate the truck market as electric powertrains. Register for CCJ Symposium and separate fact from fiction as traditional truck OEMs and new players quickly launch solutions and draw new battle lines in the race to challenge diesel’s dominance. May 21-23, 2018, Hilton Head Island, South Carolina.

Register now.

“The idea that a commercial vehicle needs to be able to overtake vehicles from 0-60 is really a consumer concept,” he says. “The commercial vehicles we’re dealing with have been tuned down to such a degree that it becomes a very capable vehicle from an acceleration perspective, but not something that is going to increase the wear of the tires. We see an equivalent amount of tire wear in the commercial sector.”

Torque availability can be dialed up through software tuning but Nordh says the emphasis to-date has been on extending range rather than boosting output.

“If you then allow them to drive like a sports car, you’re going to reduce that range capability, which is not the goal,” he says.

While long-haul carriers may not necessarily have to make a business case for electric trucks in the near term, Nordh says it’s crucial to start looking into the technology and understanding how viable it is across all applications.

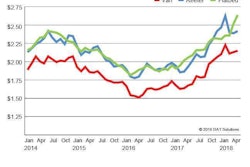

Uncontrollable and unpredictable outside factors like the future cost of diesel can make this process tricky.

“In the Class 5 [and above] market, just the commercial space in general in North America, requires the financial equation to make sense in order to make sense for adoption to accelerate,” Nordh says.

Nordh suggests looking at historic diesel costs and a given truck’s MPG performance, and then consider the additional costs of the electric infrastructure – like the charger itself and the cost of electricity.

“And then it’s looking at how many kilowatt hours am I going to need to purchase,” Nordh says. “In my opinion, based on the speed of which battery packs are becoming cheaper, and the speed at which diesel fuel and diesel vehicles continue to become more expensive, it’s just a question of ‘when’ as opposed to ‘if.”