When the topic of driver fatigue comes up, National Traffic Safety Board (NTSB) Senior Crash Investigator Mike Fox has some tough stories to tell about drivers and the carriers they work for failing to have an effective fatigue plan in place to prevent deadly and costly accidents.

One of the worst fatigue-related crashes involved a tractor-trailer heading out of Florida bound for Kentucky on Interstate 75. The incapacitated driver made plenty of headlines the night of June 25, 2015 when he crashed into several vehicles in a congested work zone in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

“The driver failed to stop, struck nine vehicles resulting in six fatalities and four injuries,” Fox said during an NTSB webinar this week on managing driver fatigue risks. “Our investigation discovered that the driver had been on duty for 40 hours prior to the crash and at the time of the accident had exceeded his hours of service. Toxicology also confirmed that the driver was impaired from taking methamphetamine.”

Driver fatigue and drug use were cited as factors leading to this deadly crash in 2015 on Interstate 75 in Chattanooga, Tenn. (Source: NTSB)

Driver fatigue and drug use were cited as factors leading to this deadly crash in 2015 on Interstate 75 in Chattanooga, Tenn. (Source: NTSB)NTSB Senior Human Performance Investigator Dr. Jana Price, another panelist on the webinar, said that “more than one in 10 serious highway crashes are associated with driver fatigue.”

It was fatigue, according to the NTSB, that led to the high-profile fatal accident between a Walmart driver and a vehicle carrying comedian Tracy Morgan on June 7, 2014 in Cranbury, New Jersey. Fox said the crash led Walmart to make sweeping changes to address driver fatigue.

“This crash is very important to highlight because it demonstrates that even a very large carrier like Walmart that employs more than 7,200 drivers, that’s extremely safety conscious, can fall victim of the dangers of fatigue,” Fox said.

The crash along Interstate 95 near Cranberry, N.J. killed Morgan’s friend and fellow comedian James McNair. Morgan was left critically injured and hospitalized along with two others who had been riding in the 2012 Mercedes Sprinter limo van.

Truck drivers involved in fatal accidents like this all have one thing in common according to NTSB vice-chairman Bruce Landsberg. “In every one of the 4,630 fatal large truck and bus crashes in 2018, every single driver was positive that it was just going to be another routine trip,” Landsberg said during the webinar. “I like to say safety isn’t everything — it’s the only thing. Because after a crash and lives have been lost, nothing else matters.”

Tough lessons learned

The Tracy Morgan crash, as Fox called it, prompted Walmart to make plenty of driver policy changes. One of the bigger problems that came to light following the wreck was that the company had no policy governing how far away drivers could live from a terminal.

“Our investigation determined that the driver had made a personal trip during his off-duty time to travel 800 miles, or 12 hours, from his terminal in Delaware to visit his home in Jonesboro, Georgia,” Fox said. “Then he drove back to Delaware, reported to work and then drove the entire route. We determined that the driver had been awake almost 24 hours at the time of the crash.”

Similar to the deadly crash in Chattanooga in 2015, the driver had failed to slow down when entering a work zone and crashed into Morgan’s limo.

Comedian Tracy Morgan was traveling inside this 2012 Mercedes Sprinter when it was struck by a Walmart tractor-trailer traveling at 65 mph in a 45 mph work zone, according to the National Transportation Safety Board. The crash claimed the life of Morgan’s friend and fellow comedian, James McNair.

Comedian Tracy Morgan was traveling inside this 2012 Mercedes Sprinter when it was struck by a Walmart tractor-trailer traveling at 65 mph in a 45 mph work zone, according to the National Transportation Safety Board. The crash claimed the life of Morgan’s friend and fellow comedian, James McNair.“Several issues contributed to this crash: first, Walmart did not have any restrictions in place to determine how far a driver could live in relation to the terminal,” Fox said. “In this case, the driver lived over 800 miles from his work location. Additionally, though the carrier had a collision avoidance system, they were not taking advantage of critical event reports that were generated for this driver.

“Lastly, although Walmart had addressed fatigue as part of their driver training, they did not have a structured fatigue management program,” Fox continued. “To their credit, after the crash, Walmart implemented numerous safety improvements that addressed fatigue.”

Walmart implemented a work commute plan that required current drivers to live within 250 miles of the terminal and new hires within 150 miles.

“Additionally, the dispatch office would send out daily alerts and safety commitment messages to each drivers Qualcomm device,” Fox said. “They also made improvements to their defensive driving training program that included instructions, such as ‘Stop if you are tired.’ Lastly, they implemented a company-wide fatigue management program. So why is it important to have a fatigue management program? Not managing the risks of fatigue could be deadly.”

An ounce of prevention

Implementing a fatigue management program can start in human resources. At a time when data abounds on just about everything and everyone, it’s best to leverage that information to avoid hiring drivers who are prone to risky behavior, which includes fatigued driving according to Harry Crabtree, corporate vice president of risk management & safety at Paladin Capital.

“Let’s not hire our fatigue problem,” said Crabtree, another panelist in the NTSB webinar. “It’s enough of a challenge without them.”

Crabtree said that Paladin’s screening process winnows out so many drivers that only 3% of applicants are typically hired.

As part of a fatigue management program, carriers should identify drivers with any health issues that could impair sleep and induce fatigue, such as sleep apnea.

As part of a fatigue management program, carriers should identify drivers with any health issues that could impair sleep and induce fatigue, such as sleep apnea.“You want to be selective. Be very selective,” Crabtree said. “The best indicator any of us have of a driver’s future performance is their past performance. Make sure the minimum driver qualification standard you have in place in your organization sufficiently screens out applicants whose record indicates the pattern for a willingness to accept risk. The sign says ‘wet paint’ and these are the type of folks that just have to touch it to see if it’s really wet. They are not risk rejectors but instead they are risk acceptors.”

Poring through telematics data daily on driver behavior and acting on that information is critical, Crabtree said. Also, don’t overlook eating habits that can bring on sleep.

“It’s been my experience, now with slightly over 40 years in this business, that if a driver is going to fall asleep, it will be within 45 minutes to 1 hour and 15 minutes after eating a large meal on the road,” Crabtree said. “Some of the most successful million mile safe drivers were always in the habit of eating small meals when on the road and not eating large banquet-type meals.”

Longtime Werner driver Bill Hambrick, who has racked up 1.7 million accident free miles, pointed out that spec’ing the right safety equipment for a truck can play a major role in a fatigue management program.

The lane departure warning system in his truck provides a visible and audible alert though the truck’s stereo. Critical events, including following distance, speed violations, hard braking, stability control and potential roll-over events, are all reported in real time to a fleet safety representative. A forward-facing camera can also help.

“It is on a continuous loop. It never shuts off,” said Hambrick, another NTSB panelist. “What happens here is that if there’s a critical event that’s initiated, it will lock in a two-minute segment of that incident and it’s immediately forwarded to the telematics system where the safety representative will take it from there.”

Other technology including facial recognition cameras can detect driver drowsiness.

“All of these are great things that can be part of a fatigue management program,” Price said. “Having incident reporting and having a way to evaluate the success of your system is critically important.”

Being mindful of driver health and medical issues that can lead to fatigue incidents should be a top priority.

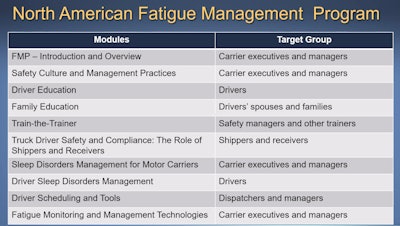

The North American Fatigue Management Program offers several training modules to help fleets more effectively combat driver fatigue.

The North American Fatigue Management Program offers several training modules to help fleets more effectively combat driver fatigue.“Sleep disorders and health issues can also affect fatigue — things like insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, and there are many other types of health issues that can interfere with sleep,” Price said. “And basically any health issue, even if it’s something like back pain or heart burn is going to interfere with your ability to have continuous sleep that can really have an impact on your alertness and your ability to stay awake along with certain drugs.”

Though most drivers understand that having a good sleep cycle can fend off fatigue, they’re often at odds with how they’re actually being impacted by a lack of sleep.

“Drivers getting four to six hours of sleep a night were tested and asked to self-report on their overall level of sleepiness,” Price said. “Initially, they reported feeling sleepy but then those reports waned as time went on.

“After a couple of days, even though their performance was getting worse and worse and worse, their self-reporting of sleepiness flatlined and stayed pretty much the same to where they were saying, ‘You know, I’m feeling OK. I’m not too much worse than yesterday.’ But their performance was worse than it was yesterday,” Price continued. “If you go multiple days with having less than optimal sleep, you may feel like things haven’t changed, but in reality your performance will continue to decline.”

Price recommended turning to the North American Fatigue Management Program for steps on implementing a company-wide approach to combating driver fatigue. The site contains 10 training modules for drivers, their families, carrier executives, safety managers and other stakeholders.

Fox said fatigue management goes well beyond complying with hours of service.

“Some people that I’ve spoken to regarding a fatigue management program think it involves a comprehensive hours of service compliance program. Well, that’s not true,” he said. “Hours of service is very important but it’s just one part of a fatigue management program. It’s very very important to understand that people are not machines and they can’t work 24 hours a day.”