Predicting truck manufacturing is the equivalent to trying to catch knuckleballs in a baseball game. Bob Uecker said, “The way to catch a knuckleball is to wait until it stops rolling and then pick it up.”

The best way to predict truck sales is to wait until the trucks are delivered.

Time is the enemy of truck demand predictions. No one is in control of all the factors that impact truck demand. How many times in the last few years have you read that "the market is recovering”? Sage prognosticators have had a tough time accurately forecasting the truck market.

In 2008, the nuances of mortgage rate financing crashed the entire world economy. No one ships mortgages by truck, yet somehow that banking debacle impacted trucking demand in big ways. Demand for new trucks in 2009 sunk to new depths.

Similarly, the dot-com bubble bursting in 2000 combined with the destruction of New York’s World Trade Center in 2001 and the start of the War on Terror crashed the trucking market. The COVID-19 pandemic had the unexpected result of increasing demand for freight hauling as people greatly increased e-commerce orders. Later on, the supply chain challenges that COVID created for key items like microprocessor chips restricted new truck supply so dramatically that new truck orders had a 16 month lead time.

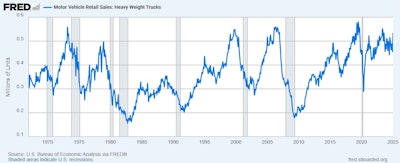

The Federal Reserve has a great graph of truck sales over the decades. What a roller coaster ride.

Smart fleets, OEMs, Tier 1 and 2 suppliers, investors and regulators probably rely on multiple predictions to help navigate the future. The assumption is that a consensus opinion arrived at by polling multiple groups will somehow magically (and correctly) forecast the economy. And yet often it’s the lone wolf visionary — the outcast — that sees the impending cliff while the herd misses it entirely.

Consensus doesn’t guarantee anything. The truck market doesn’t care what you or any other expert thinks. It’s going to do what it’s going to do.

What we control is how we deal with the volatility, how we prepare for the ups and downs to minimize the risks of market volatility.

Larger fleets have the ability to diversify their customer base to provide flexibility. If all your eggs are in one basket, what happens if there is a national bird flu outbreak and eggs are hard to get? Diversifying your customer base may mean lower profitability over time but greater long-term stability.

Specialized fleets have extra challenges. During the Great Recession, automakers had to greatly reduce car production. Customers for new automobiles were scarce. Do you remember seeing railroad sidings filled with empty car carrier railcars? Do you remember how rare it was to see a truck auto trailer on the highway? Those engaged solely in moving cars during an automotive down cycle face significant risks from market volatility. Figuring out how to successfully repurpose some of the assets is critical.

Small fleets are particularly challenged to deal with market volatility. Downturns in the industry can mean closing the doors, canceling vehicle leases, and taking jobs in other industries.

Truck manufacturers and their suppliers face major challenges with market volatility. Production capacity is tied extensively to labor. While robotic manufacturing technologies have moderated labor’s impact on factory output, people still are a large part of the equation.

Plant production lines have output limitations usually expressed in terms of line speed and shift capacity. A truck factory may normally run its production line at 10 trucks per hour. In one shift, that equates to 80 trucks per day. Ramping up that speed to respond to a sudden increase in demand initially requires asking factory workers to build more trucks per hour. The potential here is limited, adding risk that quality controls may relax resulting in downstream warranty issues.

Another way to ramp up in an emergency is to throw overtime at factory workers, extending a shift by an hour or two per day, or working weekends. The challenge here is that the entire supply chain has to accommodate that change — you can’t build trucks without parts.

If the market demand increases dramatically, plant management may consider adding a second or third labor shift. This is a major commitment and it can take months to hire and train enough people to run additional shifts. There are tooling ramifications as well, as critical capital tools may not have sufficient capacity to increase the volume of parts needed, so new tools need to be procured. Again, adding a shift has massive implications to the entire supply chain. All the part manufacturers have to add capacity as well. Freight haulers have to increase the number of loads between the suppliers and the truck maker. More trailers, more trucks, more drivers and often more warehousing.

Then just as suddenly, demand radically drops as a result of unforeseen circumstances. Plant management needs to guess whether the demand change is going to be short or long. If it’s expected to be short, they may continue to build trucks that have been ordered, hoping that demand recovers before they run out of truck orders. This is a daily struggle as fleets also start cancelling orders during a downturn. The backlog may have a lot of water in it.

If the demand drop is expected to last for a longer time, the extra shifts need to be curtailed. People are laid off. The production line is slowed. These changes impact the entire supply chain.

Predicting supply and demand of trucks is more an art than a science because there are so many factors that can impact both. Those factors are largely out of the control of the fleets, the dealers and the OEMs. Market predictions tend to be educated guesses based on the best information available at the time. And those supply and demand estimates change daily because of real-world influences.

Pricing of trucks, whether new or used, is impacted by those supply and demand estimates. A used truck in the midst of the 2021 pandemic-related supply chain shortages might have been listed for more than $100,000, while in 2024, the average might have been $58,000. How do you reliably estimate residual value of a new truck you plan to own for three or four years when that residual value can change that much based on circumstances beyond your control?

Fleets, dealers, OEMs and their suppliers all struggle with predicting the future supply and demand of trucks. As the actual market conditions shift, they have to be nimble enough, skillful enough, and flexible enough to adapt to the changes. They have to manage the risks created by market volatility.

The truck market is as predictable as a knuckleball. Fleets, truck makers and suppliers — just like baseball players — have to stay in the game to win. Learning how to deal with the pitches takes both skill and luck.