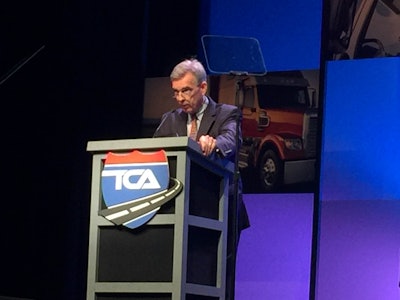

John Larkin, managing director of Transportation Capital Markets Research for Stifel, Nicolaus & Company, addresses attendees at the Truckload Carrier Association’s 77th Annual Convention in Orlando.

John Larkin, managing director of Transportation Capital Markets Research for Stifel, Nicolaus & Company, addresses attendees at the Truckload Carrier Association’s 77th Annual Convention in Orlando.If you’ve been paying attention to any of the trucking industry economists in the last two years, you’ve heard a cadence of good news: Manufacturing is making a steady comeback, construction and housing starts are up (albeit from dreadful depths), and inventories remain near historic lows. All these indicators obviously are good news for carriers, and fleets have capitalized with stronger pricing power and the desire to expand.

But a rapid growth in carrier size hasn’t materialized, thanks in large part to the driver shortage that has curtailed any desires to expand. Fleets could add power units, but they couldn’t find anyone to fill those seats.

As it turns out, the driver shortage may not be anything that the trucking industry has the power to directly control. John Larkin, managing director and head of Transportation Capital Markets Research for Stifel, Nicolaus and Company, told attendees at the Truckload Carriers Association’s 77th Annual Convention in Orlando this month that the labor force participation rate is at its lowest level since 1970.

The cause, said Larkin, is a mix of baby boomers retiring, discouraged workers and lack of opportunity. But the biggest issue is the rapid increase of entitlement programs in the last six years.

“Many trucking companies tell me that the person they are competing with for drivers isn’t other carriers, it’s the welfare state,” said Larkin. “Some of that is the function of the social welfare net that some people find it more desirable to sit on the couch and max out on welfare payments, food stamps and unemployment benefits rather than engage in an honorable profession like trucking.”

While the unemployment rate in the United States sits at 5.5 percent, well below the 10 percent it reached in October 2009 during the Great Recession, Larkin said when you factor in the under-employed (defined as part-time workers that would prefer a full-time job and over-qualified workers working menial jobs) the true unemployment rate is roughly 11 percent.

Noting that healthcare and the leisure & hospitality industries have the strongest job growth going back to August 2008, other industries such as construction and manufacturing have suffered. Larkin said there are about 2 million blue-collar jobs available in the United States. “The reality is many people that are unemployed can’t qualify for blue-collar jobs because they can’t pass a drug test or meet other minimum criteria,” said Larkin. “It isn’t a trucking-only problem that we have in the United States, the jobs are out there.”

Larkin added that during the Great Recession 22 percent of the jobs lost were low-paying jobs, but as we’ve recovered, 44 percent of new job creation are lower-paying, low-benefit jobs.

If some estimates hold true that the trucking industry will face a mammoth shortage of 250,000 drivers by 2020, the problem only is exacerbated. The silver lining, said Larkin, is that it should create a positive pricing environment.

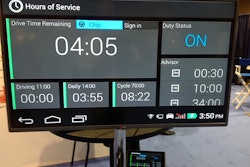

Stifel analysts currently project a 3 to 5 percent increase in freight rates this year overall. A myriad of regulatory pressures, including hours of service changes, electronic log mandate, Compliance Safety Accountability, drug testing and increased driver training requirements could create the “mother of all capacity crunches” sometime in 2017 and 2019, said Larkin, adding, “That could be exciting for everyone in the room.”

Constrained capacity could be so bad however that Larkin said it could affect the growth of the overall U.S. economy, calling that scenario “worrisome.”

“But it could also lead to more free thinking by Congress that perhaps would open up some possibilities for more productivity, including getting young driver trainees into the system before they turn 21 years old so we don’t lose all these high school graduates to other industries,” said Larkin.