In 2004, rising truck tonnage, tight capacity, lean inventories and improved freight pricing helped ignite a driver shortage that swelled to more than 100,000 over the next two years. The result was higher driver pay and big sign-on bonuses. While a tight driver supply gives carriers – and drivers – leverage, a shortfall of drivers this time around could prevent many fleets from capitalizing on available freight and cause disruptions to supply chains.

Market conditions today – while not as robust as seven years ago – are comparable, but the unfolding driver shortage is expected to be much more severe, with some analysts predicting a shortfall of up to 400,000 drivers by the end of 2012.

Chief among the factors expected to curb driver availability are new federal regulations, including the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s new Compliance Safety Accountability program and pending changes to the hours-of-service rules, as well as driver training capacity limits and an aging population of drivers within striking distance of retirement.

A generational issue

A study during the last driver shortage by Global Insight, commissioned by the American Trucking Associations, shed some light on the industry’s aging driver population. One in six truck drivers was over the age of 55, and 43 percent of all truck drivers were at least 45 years old. While the study was based on analysis of 2000 Census data, meaning that core group is now out of the industry or on the verge of retirement, the findings remain valid today. More than one in three company drivers are 55 or older, according to a 2010 study by CCJ’s sister publication Truckers News, and only 6 percent are under 35.

“The average age of a driver at our company is 54 years old,” says Tommy Hodges, chairman of Shelbyville, Tenn.-based Titan Transfer and immediate past ATA chairman. “I have maybe eight to 10 years in that driver’s life left to drive a truck. Who am I going to get to replace him? The demographics are against us.”

According to the Commercial Vehicle Training Association, the average age for new entrants to the truckload segment is currently 41 years old, and the average age for the less-than-truckload segment is 56.

Compounding the problem of an aging driver force, conditions will be “very negative” for finding new drivers, says FTR senior consultant Noël Perry. With the end of the Baby Boom generation, the number of people available to trucking to replace those retiring will drop to about 500,000 a year from 2.5 million during the last decade when the downturn in construction and offshoring of manufacturing increased the available labor pool. He adds that tougher immigration laws would keep many other potential drivers out of trucks compared with the last decade.

In addition, many truckers who were laid off during the recession either have left the industry or have found jobs with other carriers, says Perry. “It’s going to be fundamentally harder to recruit people.”

Training bottleneck

Perhaps the biggest constraint on driver availability is the industry’s ability to train and qualify new entrants. At its peak, the driver training pipeline is estimated at 150,000 per year. During the last recession, however, many carriers cut back recruiting programs or eliminated them entirely, creating what Perry refers to as a “cyclical drag.” Currently, it’s estimated that the industry can train about 100,000 drivers per year, well short of what will be needed in the near term.

“Some of the largest in-house schools are gone, and we’ve gutted our ability to recruit and train large numbers of drivers,” said Gordon Klemp, president of the National Transportation Institute, during a Commercial Carrier University session at the Truckload Carriers Association’s 2011 Annual Conference. “Rebuilding this will take time and reengineering of the job.”

Mike O’Connell, CVTA executive director and counsel, says the driver training industry also is under siege from federal funding cuts and new regulations.

In its May final rulemaking on tightening testing standards for states to issue commercial learner’s permits, FMCSA added a provision that with limited exceptions prohibits third-party skills examiners from testing applicants they trained. The provision “will work an extreme hardship on both the trucking industry and on driver training programs at a time when there is a deepening shortage of entry-level commercial drivers,” according to a petition filed by the CVTA, Professional Truck Driver Institute, ATA, TCA and other industry groups.

To make matters worse, a rule scheduled to come out this fall would set minimum requirements on training hours and require accreditation. “That will put an enormous burden on the industry,” O’Connell says.

Regulatory pressure

When CSA finally rolled out late last year, it was a game changer for carriers that don’t put a premium on safety. For the bad apples in the driver population, CSA is a death sentence, as negative driving records will render them virtually unemployable.

“We’re all interested in highway safety,” says O’Connell. “CSA is a good idea. It will bring better drivers in, but it will have an impact on how many can come in.”

Just how big of a limitation will CSA be for driver availability? In a recent survey of more than 300 fleets, nearly three out of four respondents said they expect CSA to reduce the driver pool between 4 and 8 percent.

In addition, FMCSA’s proposed changes to the HOS regulations could put a serious dent in driver productivity if the driving window is shortened from 11 to 10 hours, creating an even greater stress on driver availability. Strict enforcement of HOS rules and the proliferation of electronic onboard recorders will limit driver productivity further and turn away potential candidates from the industry.

The effect of new regulations on driver availability won’t manifest itself this year, but by the time CSA’s impact is realized fully and the new HOS regulations take effect, “there will be the equivalent of 300,000 drivers taken out of an industry that employs 2.8 million,” says Perry. “FMCSA has been slow to publish and make these changes official. What that has done is concentrate all these changes next year. We’ll need 10 percent more drivers next year than this year. When paired with the cyclical drag created by laying off recruiters, that will reach 400,000 by next year.”

Finding a solution

While the industry searches for answers to combat the driver shortage, many fleets worry about repeating mistakes from the past. The wrong path, says Hodges, is to repeat the “churn” that occurred in 2006 and 2007 by throwing money at the problem with inflated pay rates and sign-on bonuses. “It’s cannibalistic to continue to do what we’re doing, me hiring your drivers and you hiring my drivers – it’s futile, but that’s where we’re at.”

And driver pay is rising, already at or above its previous highs in 2006. NTI routinely tracks the pay landscape in its National Survey of Driver Wages. Recently, anticipation of regulatory changes and other factors led to striking results to a particular question, says Klemp. When asked whether they expect to raise pay for drivers in the next year, about 80 percent of fleets said yes. “I think the value of drivers will go up,” says Klemp. Dry van and flatbed pay, which declined during the recession, already is bouncing back, and “an awfully high percentage of carriers have instituted referral or sign-on bonuses.” Many also are turning to owner-operators to meet demand. (See “Rising Stars,” page 60.)

As pay and incentives improve, ATA’s most recent quarterly trucking activity report indicates driver turnover rates already are increasing. According to the survey, in the first quarter of this year, turnover for line-haul drivers at large fleets rose to 75 percent, up sharply from a record low of 39 percent from a year ago, although still nowhere near the 100 percent-plus turnover rates common in years past.

While turnover indicates movement within the existing driver population, the real problem remains how to bring new entrants into the industry. Some carriers see elevating the image of truck driving as a career as one way to improve application rates.

“We do a very good job of promoting trucking’s image inside our industry, but the outside world doesn’t see any of that,” says Brian Kinsey, chief executive officer for Brown Trucking, based in Lithonia, Ga.

In an effort to improve the driver’s image, Brown Trucking executives refer to them only as “commercial vehicle operators.” What sounds like a small change can have a big impact on the way drivers view themselves and how other groups within the organization perceive them, Kinsey says. “We demean the people who run our trucks by calling them ‘drivers,’” he says. “The guy that operates a plane isn’t a ‘plane driver.’ The guy that runs earthmoving machinery isn’t called a ‘dozer driver.’ Calling them drivers implies their job is something that anyone can do, that it’s a nonskilled job.”

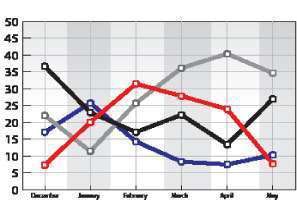

Driver availability tops fleet executives’ concerns

Ranks well ahead of freight pricing, volume

Gray — Driver/Labor Availability

Black — Freight Pricing

Blue — Freight Volume

Red — Fuel/Energy Costs

On a national scale, TCA has taken a leadership role with its revitalized image program in an effort to change public and media perception of the trucking industry and its drivers. It includes a biweekly spot on a nationally syndicated radio program, a new Wreaths Across America commercial and greater exposure for its Highway Angel program. “When it comes to image, we’re in the driver’s seat of our own destiny,” says Gary Salisbury, president and chief executive officer of Hope, Ark.-based Fikes Truck Lines and TCA chairman. “If we don’t grab the wheel, somebody else will.”

As far as what individual carriers can do to make a career behind the wheel more appealing to new applicants, some analysts suggest tailoring routes to fit drivers’ lifestyles. “One thing fleets can do is show people that there is a career path,” says O’Connell. “They may start out driving all over the country, and as they build credibility in terms of service, reliability and safety, they can go on more regional runs, then to dedicated runs where they’re home more often.”

Some analysts predict a shortfall of up to 400,000 drivers by the end of 2012.

Carriers also can work closely with shippers to help maximize driver productivity, including conversion to drop-and-hook operations or expedited loading and unloading at docks to reduce wait times. Another solution, says Perry, is for carriers and shippers to share information to coordinate loads closely and take advantage of empty trucks.

Even as the economy slowed and freight softened slightly in the second quarter of this year, capacity remains relatively tight. An aging driver work force, looming regulations and reduced ability to recruit and train new entrants to the market are coming together at the same time to create what many are calling a “perfect storm.” How the industry responds to the driver shortage crisis is yet to be determined, but carriers that avoid the mistakes of the past and are proactive in their recruiting and retention efforts will be the ones best positioned to take advantage of available freight in the future.

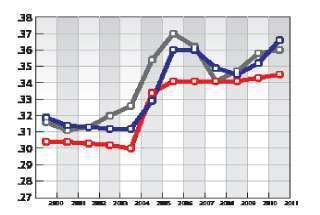

Company driver pay on the rise

Solo new hire with three years experience by segment

Blue — Dry Vans

Gray — Flatbeds

Red — Refrigerated

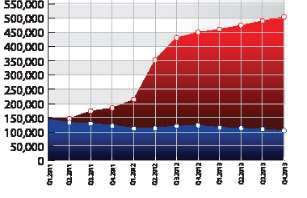

The worst is yet to come

The real impact of CSA and changes to hours-of-service rules will be felt next year.

Red — Regulatory Drag

Blue — Cyclical Drag

Rising stars

Carriers look to owner-operators to fill driver gap

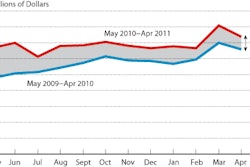

Improving freight levels and tight capacity have led many carriers over the past two years to turn to owner-operators to help them meet demand. During the still uncertain recovery, many carriers view owner-operators – who offer built-in capacity, a strong work ethic and a reputation for good customer service – as a smart alternative to expensive company equipment. In fact, more than 42 percent of fleet executives responding to the May Randall-Reilly MarketPulse survey said they plan to add independent contractors in the next six months. While that’s down from the 62 percent who were looking for owner-operators at the end of last year, competition still remains fierce.

Such demand means “owner-operator pay is poised to take off” and could increase as much as 6 cents per mile over the remainder of this year, says Gordon Klemp, president of the National Transportation Institute, which tracks driver pay. As freight rates increase, owner-operators paid on a percentage also will benefit.

Many carriers, such as Granger, Iowa-based Barr-Nunn Transportation, already have started to bump pay. A series of increases has brought Barr-Nunn’s basic owner-operator pay package to $1 per loaded mile, a figure Klemp calls “pretty aggressive.” Director of Recruiting Jeff Blank says he has seen “a good impact” to his recruitment efforts from the increases and a $1,500 sign-on bonus.

More carriers already would have raised pay but for one missing factor: churn. “Many owner-operators are still convinced the economy is fragile, and because of that, they don’t want to change jobs if they feel they are with a secure carrier,” Klemp says. “The economic picture is not bright enough for them to move. If that changes, I think we’ll probably see wages – and churn – really pick up.”

More carriers also will offer lease-purchase programs, Klemp says, in an effort to grow their own owner-operators. Barr-Nunn’s program, launched in 2009, more than doubled the number of owner-operators leased to the carrier. Another benefit: “Turnover has been excellent,” Blank says.

Crete Carrier Corp. of Lincoln, Neb., plans to “help as many of our drivers become owner-operators” as have the desire to do so, says Director of Recruiting Richard Snyder. Crete had stopped hiring owner-operators during the recession and focused instead on keeping the ones it had. But today the company is adding owner-operators and is in the process of revamping its lease-purchase program.

Carrier lease-purchase programs are one way to regain owner-operators lost during the recession. Since 2008, the number of owner-operator businesses has dropped about 6 percent, according to CCJ’s sister publication Overdrive, which has been tracking this data for more than a decade. (To place that in the context of the larger for-hire population, more than 6 percent of carriers with five or more trucks have filed bankruptcy since 2008, according to analysis of Avondale Partners data and Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration census numbers.) The good news is that the owner-operator market is cyclical: After falling by more than 10 percent during the last recession, the population quickly rebounded and by 2004 had reached its pre-recession level.

This time around, though, the barriers to entry are higher due to a limited supply of late-model used trucks and a tight credit market, says Todd Amen, president of owner-operator business consultant firm ATBS. For the next couple of years, lease-purchase programs may be the best alternative for aspiring owner-operators to get into the business, Amen says. “If I want to be an owner-operator, I can get into one of those trucks fairly easily,” often with no money down and no credit check.

Longer term, however, Klemp sees owner-operator buying power returning. “Owner-operators have had a tough time, but have done a fabulous job of maintaining cost controls over the recent economic downturn,” he says. Pay and freight rate increases will further improve existing owner-operators’ business outlook and will make the business model more attractive for new entrants, he says. “We think the future’s bright.”

– Linda Longton and Avery Vise

– Todd Dills and Max Kvidera contributed to this article.