| Major changes to HOS rules

Effective July 1, 2013• Restart: Retains the 34-hour restart provision, but adds it must contain two consecutive periods from 1 to 5 a.m. • Restart limit: Caps the use of the restart provision to once every seven days. • Mandatory resr break: Drivers may drive only if eight hours or less have elapsed since the end of the last off-duty period of at least 30 minutes. Effective Feb. 27, 2012 • On-duty time: Does not include any time resting in a parked CMV. For team drivers in moving CMVs, does not include up to two hours in passenger seat immediately before or after eight consecutive hours in sleeper berth. • Penalties: Defines “egregious” penalties as driving three or more hours beyond the driving time limit; fines up to $11,000 per offense for fleets, $2,750 for drivers. • Oilfield exemption: Does not count time spent waiting at oil well or natural gas site toward 14-hour on-duty window. |

Armed with a mandate to combat driver fatigue to improve motor carrier safety and backed by a collection of often-criticized data and research, FMCSA issued its long-awaited HOS notice of proposed rulemaking in December 2010. After a year of contentious debates and scathing public comments, FMCSA released its HOS final rule on Dec. 22.

Though the agency scaled back some of the NPRM’s provisions, the final rule still contains substantive changes to current hours requirements. Industry groups now argue that the provisions in the new rule threaten productivity and question the impact it will have on reducing truck-related crashes. Safety advocacy groups decry the new rule as not doing enough to lower crash risks.

11th hour retained

In a “win” for the trucking industry, the HOS final rule retains the 11-hour daily driving limit, providing flexibility for drivers who encounter unexpected delays. FMCSA, which had favored a 10-hour daily driving limit throughout the rulemaking process, stated an “absence of compelling scientific evidence demonstrating the safety benefits” for lowering the limit. But the agency hasn’t closed the door entirely on reducing the driving limit in the future; it will continue to conduct further data analysis and research to examine risks associated with the 11-hour limit.

“While the vast majority of truckers and companies don’t use the 11th hour to its max every day, it’s nice to have as a buffer,” says Dave Osiecki, senior vice president of policy and regulatory affairs for the American Trucking Associations. “In some cases, it has increased productivity, particularly in dedicated operations.”

Safety advocacy groups, meanwhile, had been optimistic that FMCSA would lower the daily driving limit to 10 hours and immediately blasted the new rule.

“Since the Department estimates that 500 people are killed each year in truck driver fatigue-related crashes, leaving this provision in the rule is unconscionable,” says Henry Jasny, vice president and general counsel for Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety.

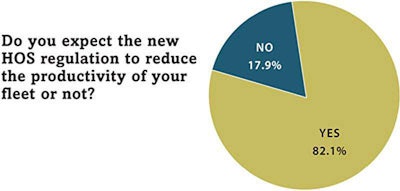

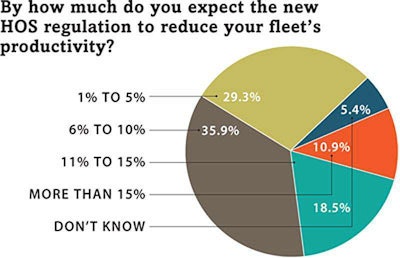

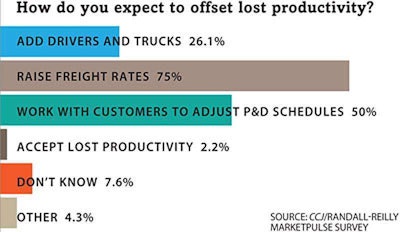

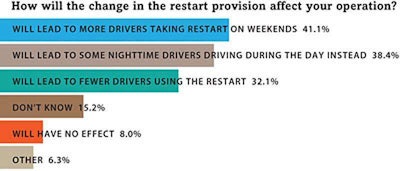

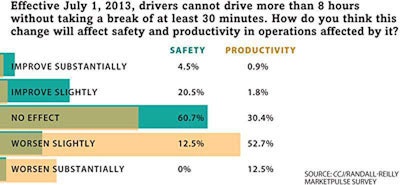

| Fleets respond to new HOS rule

Carriers largely feel that the new HOS FINAL rule will have little impact on improving trucking safety. CCJ conducted a survey of fleet executives to get an early look at where carriers stand on various aspects of the new rule. (based on 120 respondents) |

“I am beyond disappointed that, once again, industry profits were put before the safety of the motoring public and truck drivers,” says a spokesperson for the Truck Safety Coalition.

Unintended consequences

The change to HOS rules that has drawn the most criticism from carriers is a new restart provision that adds two consecutive 1-to-5 a.m. periods to the existing 34-hour restart to force nighttime drivers that bump up against the 60- or 70-hour workweek to get two nights of “restorative” sleep. Also, the final rule limits use of the restart to once per week, effectively cutting the maximum workweek from 82 hours to 70 hours on average.

“A key issue I see that makes this regulation a step backwards on safety is that more drivers will be driving during the day on already-crowded highways,” says Ray Kuntz, chief executive officer for Watkins & Shepard Trucking, a less-than-truckload and truckload carrier based in Helena and Missoula, Mont. The fear, says Kuntz and other carriers, is that truck-involved crashes actually may increase as a result of the new restart provision.

Steve Keppler, executive director of the Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance, says the issue is compounded when considering crash risk in relation to drive time. “You have increased mixed traffic, and the research shows most crashes occur in the first two hours of coming on duty – it’s a legitimate concern,” he says. “FMCSA doesn’t think many drivers will need to use the restart, but I’ve heard differently. A number of folks have expressed that concern.”

Drivers who work heavy and irregular hours likely will be impacted the most by the new provision. If these drivers schedule their restarts during the weekend, it will lead to a greater number of drivers hitting the road at the beginning of the week in early rush-hour periods when the second 1-to-5 a.m. period is complete. “That is going to put them into the traffic stream at a time the public doesn’t want them in the traffic stream,” says Osiecki.

FMCSA says most drivers that work at night – primarily LTL and local delivery – don’t accrue enough hours to require restarts and that truckload drivers don’t drive at night routinely and have more flexibility to adjust start and stop times to minimize the provision’s impact on their operations. By moving the end of the restart period from 6 a.m. in the NPRM to 5 a.m. in the final rule, the agency says it will lessen the impact on rush hours.

Timing a restart also is a concern for fleets trying to maximize driver productivity. Only if a driver begins a restart period between 7 p.m. and 1 a.m. will the restart truly be 34 hours when he’s eligible to come on duty between 5 a.m. and 11 a.m. two days later. If a driver runs out of weekly hours at 2 a.m. and begins a restart period, he will be unavailable for 51 hours until his restart ends.

Take a break

Another significant change in the HOS final rule is a provision that drivers cannot drive after working eight hours without taking a 30-minute break. (FMCSA was considering a seven-hour on-duty window.) The provision effectively reduces the maximum on-duty time within the 14-hour work window to 13½ hours. If a driver plans to drive until the end of the 14-hour window and takes a break within the first 5½ hours since coming on duty, a second 30-minute break would be required, reducing his workday to 13 hours.

Other problems the trucking industry has with the 30-minute break is the likelihood of increased parking congestion and the fact that the 30-minute clock only starts when the driver goes off duty. “It actually will be longer than 30 minutes because the driver has to get off the interstate, drive to a safe area and find a place to park,” says Osiecki. “That 30-minute period can quickly become 45 minutes or even an hour, so the productivity loss is probably bigger than what FMCSA suggests.”

FMCSA countered in its final rule, “If drivers are averaging less than 50 hours of driving a week, it is difficult to understand how a half-hour break taken sometime between the second and eighth hour in a 10-hour day could cause delays unless the industry is saying these drivers never stop for a meal or rest break during that time.”

A productivity hit

In its Regulatory Impact Analysis, FMCSA estimates the HOS final rule will have net benefits of $205 million but that productivity will be reduced by 1.2 percent. ATA believes the productivity loss estimate should be doubled; carriers that have crunched the numbers believe it could be worse.

“Carriers have talked about anywhere from a 6 percent to 15 percent loss in productivity, and the reason there’s a difference there is because this rule hits different applications in different ways,” says David McCorkle, chairman of Oklahoma City-based dry bulk hauler McCorkle Truck Line and member of ATA’s HOS committee.

Of the 120 respondents to a CCJ/Randall-Reilly MarketPulse survey of fleet executives following the final rule announcement, 75 percent expect to raise rates to respond to lost productivity. (See “Fleets respond to new HOS rule,” page 46.) Shippers and manufacturers predict the new HOS rules will impact supply chain management negatively and drive up consumer costs.

“Manufacturers have built their logistical operations based on the current rules and have invested in compliance since their implementation,” says Jay Timmons, president and CEO of the National Association of Manufacturers. “To change these rules and limit the flexibility of manufacturers without sufficient reasoning is a mistake and will impede the ability of manufacturers to invest, grow and create jobs.”

“Retailers’ ability to move goods efficiently has changed the retail landscape and benefited consumers by reducing prices and increasing product assortments,” adds Kelly Kolb, the Retail Industry Leaders Association’s vice president for government relations. “The new rule will upend the advances in efficiency over the past decade.”

Compliance, enforcement, litigation

During the NPRM public comment period last year, many carriers and industry groups argued that complex changes to HOS rules would increase the difficulty of compliance by carriers and likely would be too complicated for the average truck driver, leading to inadvertent logging errors or an increase in log falsifications. FMCSA responded to these concerns by simplifying the final rule, but the new provisions unquestionably are more complex than the current rule.

Law enforcement groups also raised concerns, namely the ability to train personnel to enforce the new rule uniformly from state to state. “You can have the greatest rule since sliced bread, but if it’s not enforceable, what good is it going to do?” asks Keppler.

One solution, he says, is to change the supporting documents requirements. Depending on when a restart is initiated, “we can’t see back far enough based on what the driver is required to retain,” says Keppler. “We can’t verify the legitimacy of the restart period, and that’s an issue. The two biggest things FMCSA can do is mandate electronic onboard recorders and require supporting documents to be maintained on the vehicles.”

CVSA also is concerned that the more prescriptive the rules are, the more likely bad actors will falsify logs. Take, for example, the new on-duty time definition that allows drivers not to count time resting in a parked truck or two hours in the passenger seat immediately before or after eight consecutive hours in the sleeper berth. “How do we know that? Were they loading or unloading? Were they fueling?” asks Keppler. “That is the difficulty – that two hours is not an insignificant amount of time.”

Considering the amount of opposition to the HOS final rule, litigation from safety groups, the trucking industry and labor is more likely to happen than not. “If there is a positive in this rule, it is the lengthy period of time before it becomes effective,” says Bill Graves, ATA president and CEO. “This will give us time to consider legal options.”