In one word this challenge can be described as “scale.” For any technology to work, it has to be scaled up or scaled down in order to satisfy a specific set of business requirements.

When writing about technology, it’s critical to understand the needs of your audience. Likewise, software developers have to understand the different needs in the market. Fleets also have to evaluate their business needs and scale their technology budgets accordingly.

Software developers have to evaluate whether their technology can be scaled to meet the needs of a fleet of 10 vehicles versus a fleet of 100 vehicles? Fleet owners have to evaluate if the technology is too simple or too complex with more bells and whistles than they are willing to pay for.

Consider routing and scheduling technology. Theoretically, any size of fleet could benefit from knowing the most economical way to meet their pickup and delivery schedules. Due to the cost and complexity of these systems, the scale would seem to lean towards large fleets. But that’s not necessarily the case.

Here’s one example of how routing software can be scaled to a fleet of 10 vehicles. If the fleet could use the software to create a set of routes to meet its daily demand with one less vehicle or driver, that’s real savings. Even if the company had to spend several thousand dollars for the software, that’s minimal compared to the cost of equipment, fuel and driver wages. The fleet would get an immediate savings of 10 percent and, over time, be able to trim more mileage and fuel costs from the rest of the fleet.

Salter says that Paragon Software typically can save fleets between 10 and 25 percent by eliminating excess vehicles and mileage from their routes. Overall, more than 750 fleets around the world are using Paragon Software for routing vehicles. Its customers range in size from as few as 10 trucks to over 1,000.

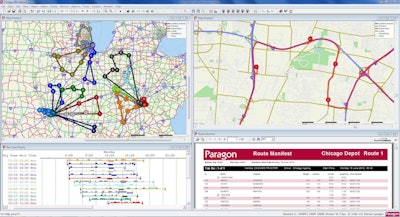

Paragon’s software can be scaled according to customers’ needs, he says. Fleets on the small end of the scale might choose to install the software on a stand-alone PC and input orders manually. On the larger end, companies can link Paragon’s routing software to their order processing, warehouse management, in-cab telematics, and reporting systems to automate their planning and routing workflow from beginning to end.

Most customers that use the software operate private fleets, typically in a local or regional network to distribute products such as industrial gases, beverages, food, and car parts, he says.

One of Paragon’s recent customers in the U.S. is Goody Goody Liquors. The Dallas-based liquor store chain operates 27 retail locations and 6 wholesale locations that service between 600 and 700 hotels and restaurants in Dallas, Houston and Longview, Texas. The company serves each of these locations with a fleet of 35 trucks located at three distribution centers.

Goody Goody Liquors purchased Paragon’s Single Depot transportation planning software and plans to use the new technology to develop and implement more efficient transportation schedules.

In writing about technology, some of the most fascinating topics such as “data mining” or “optimization” are often beyond reach for small fleets. In the case of routing software, the scale of this advanced technology extends from the largest fleets all the way down to fleets with as few as 10 vehicles.