CHART: The New York Times

CHART: The New York TimesI sympathize with fellow journalists looking for blog fodder, and I appreciate the efforts by anyone outside of trucking who thinks he’s got the industry figured out, whether it’s truck safety or the business model or the need for a shift to rail: These attempts always give me something to write about as well.

The latest try comes from The New York Times and The Upshot column, conceived to provide “news, analysis and graphics about politics, policy and everyday life.”

For a starting point, The Upshot this weekend, “The Trucking Industry Needs More Drivers. Maybe It Needs to Pay More,” takes a look at a recent one-day tumble in the stock price of Swift Transportation (No. 3 on the CCJ Top 250), dropping 18 percent after earnings came in lower than expected.

The problem isn’t that the company doesn’t have enough customers and freight; rather, it has more than it can handle and the bottleneck is the supply of drivers.

“But in a time of elevated unemployment … how is that possible?” author Neil Irwin asks.

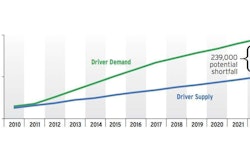

He goes on to note the often-quoted American Trucking Associations estimate that the industry will be short some 200,000 drivers over the next decade.

Still, that level of shortage “flies in the face” of the U.S. unemployment situation, to say nothing of basic economics, the piece explains: Pay drivers more and they will come.

“But corporate America has become so parsimonious about paying workers outside the executive suite that meaningful wage increases may seem an unacceptable affront,” Irwin writes. “In this environment, it may be easier to say ‘There is a shortage of skilled workers’ than ‘We aren’t paying our workers enough,’ even if, in economic terms, those come down to the same thing.”

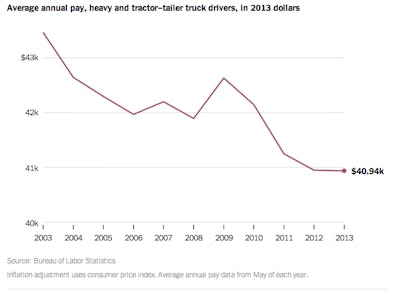

The “revealing” numbers: Tractor-trailer driver drivers made 6 percent less in 2013, adjusted for inflation, than they had a decade earlier. (My math on this, based the BLS data, actually shows a 5.7 percent increase in adjusted wages between May 2003 and May 2013 – but let’s not quibble and I promise to double check soon, or to consult an expert.)

Still, “It takes a peculiar form of logic to cut pay steadily and then be shocked that fewer people want to do the job,” he says.

Additionally, the analysis notes that driver wages come in on the high side for work – hard work, to be sure – that doesn’t require a college degree. And the basic job qualifications can be learned quickly, especially when the driver problem is compared to worker shortages in industries that need people with years of specialized training.

But, as ATA Chief Economist Bob Costello explains to Irwin, the situation is complex, and to build a case simply around driver pay is “not quite fair.”

Safety regs such as the hours-of-service rule have reduced average driver miles to 8,000 a month, down from 11,000 in 2007, according to the story. Trucking companies likewise operate on thin margins, and driver wages are a key component in bids on long-term shipping contracts.

But rather than dig deeply into the complicated issue, Irwin uses the driver shortage to illustrate his big picture point: “a mind-set in which executives sometimes think of line workers as merely resources to be tapped at the lowest price.”

Technological change, globalization and a decline of union power all have contributed to generally stagnant wages for “workers without advanced skills,” he argues, and the great recession and slow recovery prolonged the trend. (I’d add shareholder pressure generally, and rate competition in the highly fragmented trucking industry specifically.)

Bottom line: Wage income has slipped to the same percentage of gross domestic product as it was in 1947, while corporate profits are at postwar highs.

Yet something has to give, Irwin contends. “The shortage of truckers is one piece of evidence that the balance of power is shifting.”

He notes rising wage pressure across a range of industries, and points to the use of sign-on bonuses in trucking. His conclusion: Higher pay for the workforce is “a welcome corrective.”

“When workers begin to have more leverage in salary negotiations, it is a sign of an improving economy, not a liability that businesses should be complaining about,” Irwin says.

Of course, none of this should be news to carrier management, and it’s a vastly simplified argument.

First, I’d like to overlay a chart of carrier rates from that same period of stagnant driver wages – and I’ll look around to see if I can find one. And any analysis of the trucking industry that doesn’t mention the rise in the cost of fuel is missing a critical piece.

Adam Smith

Adam SmithOn the other hand, for those inclined to give the original analysis of modern economics some credit, Adam Smith in his Wealth of Nations explains that wages are indeed a tricky matter: Good wages and the prospect of a better life tend to encourage good work, and labor will migrate to good wages.

But he has words of caution regarding the risk of overwork when labor is rewarded at a piece rate: “Workmen, when they are liberally paid by the piece, are very apt to overwork themselves, and to ruin their health and constitution in a few years,” Smith writes. “If masters would always listen to the dictates of reason and humanity … it will be found, I believe, in every sort of trade, that the man who works so moderately, as to be able to work constantly, not only preserves his health the longest, but, in the course of the year, executes the greatest quantity of work.”

And the debate, in trucking, continues. But it’s a mistake to suggest that the industry isn’t trying desperately to find a solution.

An overweight load of CCJ driver shortage coverage is here.