The large center-mounted, touch-screen display controls everything.

The large center-mounted, touch-screen display controls everything.If there was a polar opposite of a tractor trailer, Tesla‘s Model S just might be it. The sporty sedan is limited to whatever cargo capacity five people can wedge into its front storage compartment – the “frunk” – or and the traditional rear trunk compartment.

But, as I made my way to Los Angeles this week for the Thursday debut of Tesla’s electric semi truck, I couldn’t turn down the opportunity to drive one of the cars that served as validation for many of the technologies found in the semi prototype. Of course, it didn’t hurt that it was a Model S P100D – “the world’s quickest production car” – with a zero to 60 time of 2.5 seconds and the top of the performance heap in Tesla’s S series.

The car is rich with un-car-like technology. It looks like a car and acts like a car but its processes are on a different level. I’ve never thought of Tesla as a car company. They’re a technology company that makes cars, and I think that becomes evident from the moment you flop down into the driver’s seat and try to wrap your mind around the Model S controls.

The car is on from the moment it recognizes that you – more importantly, the key – is near it, but it’s not ready to drive until you put your foot on the brake. That’s how you signal to the car it’s time to go. The gear shift is mounted to the console on the right, and you push up or down to select drive or reverse. A button on the end of the stalk puts the car in park. After selecting your gear, you simply press the accelerator and away you go. You just have to trust that the car is on because it’s not making any noise.

It is equipped with a creep mode, which moves the car forward at idle-speed once you lift off the brake but there is no idle in the traditional sense. With an electric car, idling is much more black and white: it’s either moving and consuming energy or it’s not, which also means there’s no fuel wasted. An hour of idling burns about one gallon of diesel fuel. If your fleet spends as much time fighting traffic as it does delivering goods, electrification wipes out expensive waste, not to mention that idling increases wear on a truck’s engine. I’ve seen estimates that suggest idle reduction technologies could reduce fuel usage by about 1 billion gallons a year – a savings of about $3 billion in fuel costs. With Tesla’s technology, idle hasn’t been reduced, it’s been eliminated.

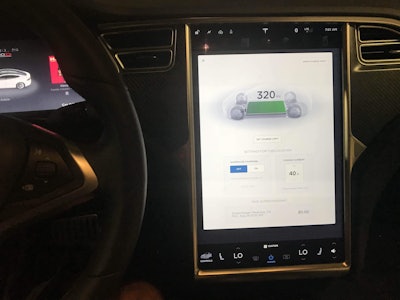

A large, center-mounted, touch-screen display is overwhelming at first. It controls everything. Like the world’s largest and most powerful mobile phone, it’s the brains of the car you’re driving. From the air conditioning to the sunroof to the radio to the navigation, the giant iPhone-like screen houses all the mission critical stuff for the car, including programming and customizing its air suspension.

It takes a few minutes to get comfortable with it all, what all it can do and how to find it, but after a while it all becomes less imposing and more intuitive.

The instrument cluster is clean and organized but has no dials or gauges.

The instrument cluster is clean and organized but has no dials or gauges.I mostly used the screen for Google Maps because I had no idea where I was or how to get where I was going, and the giant display was very helpful in that regard. The instrument cluster is clean and organized, offering a wealth of information, including a smaller, more stripped down version of the map which kept me from constantly looking to the right. Otherwise, there are no dials or gauges, just big, bold and bright numbers or graphs. Obviously, instead of a fuel gauge, there’s a battery level display.

I don’t think the integration of an electronic log into the touch-screen is a large hurdle to clear. In fact, Tesla says it can flash one over the air to the truck via an update. All of the technologies fleets need to run their business could be brought into one package, eliminating the need for multiple platforms and plug-ins.

If you’re not used to an electric vehicle, I think it’s natural to suffer range anxiety. When Tesla handed over the digital key, the car had 276 miles of energy left and I was already wondering what I was going to do when the battery died. Not if. When.

But as the miles ticked along, that concern drifted away. Seemingly every third car on the 405 was some kind of electric, and if they could figure it out so could I. I drove the car all Wednesday night and barely gave range much thought, only glancing at the digital display a handful of times – about as often as I would to check my fuel level. When I got back to the hotel about four hours later, my range was around 230 miles.

My Model S featured regenerative braking, which captures friction energy from the car’s brakes and pumps it into the battery supply. If you’ve never driven a vehicle with regenerative braking, it’s a unique experience. Basically, whenever you lift your foot off the accelerator the brake begins to kick in. The drag feels a lot like it would if you had applied the foot brake, and you have to learn how to drive with it or you wind up fighting it. If you lift too soon, you’ll almost always stop sooner than you think. I’ve found the best way to use it is to let it act as the footbrake, and only apply the brake pedal to completely stop the car. The regenerative brake supplies more than enough braking force to slow it.

You hear a lot about the on-demand torque in an electric car, mostly the phrase “full torque at zero RPM” – whatever that means. What that means is there’s no engine wind up. When you need to go, just press the accelerator and you’re gone. Immediately. The Model S P100D features three torque modes, each more asphalt gripping than the next. The car’s spine-snapping Ludicrous Mode is what makes it the 0-60 champion of the world. That’s not a function altogether handy for a semi tractor, but the ability to adjust torque on the fly as terrain and load dictate would be a handy feature.

The all-wheel drive car is powered by dual electric motors and is equipped with a 100kWh battery pack – Tesla’s largest – and features a driving range just north of 300 miles on a single charge.

The Model S is rich with cameras to support its AutoPilot feature, but uses only about half of them. The rest are included as architecture for fully autonomous driving. Whenever that becomes a “thing,” Tesla can flash updates to the car, activating the rest of the technologies that were included at build but lie mostly dormant.

AutoPilot is activated via a steering column stalk on the left side. You can opt for adaptive cruise, lane keeping assist or both for a full Level 2 autonomous experience. Similar technology is already included on many of the big rigs on the road today. Surrendering control of a moving vehicle to a network of sensors and “magic” is unnerving, but it’s important to note that Tesla’s AutoPilot is a driver support feature and isn’t designed for the driver to mentally check out. The driver still has total control of the car and can deactivate auto-steer by turning the wheel or tapping the brake.

I enabled the feature in dense traffic and adaptive cruise kept up with the pace of the cars around me, while lane centering meant I didn’t have to twitch the wheel at low speeds. There were times I took control away from the car, not because I disagreed with anything the car was doing but because I felt the need to react. Or maybe overreact. In the cases where I could power through my panic, the car did exactly what it was supposed to do every time.

This level of technology is a far cry from “self-driving,” but it’s the most logical next step toward it. It adds a layer of safety for the fleet and driver, practically eliminating the possibility of a rear end collision if you let the system do what it was designed to do: help the driver.

The parking deck at my hotel had ample charging stations, so my earlier worry about range had been for nothing.

The parking deck at my hotel had ample charging stations, so my earlier worry about range had been for nothing.Using a new high-speed DC charging solution, Tesla says you can pump about 400 miles of range back into the Semi in about 30 minutes. Chargers can be installed at origin or destination points and along heavily trafficked routes, enabling recharging during loading, unloading and driver breaks.

You can pump about 100 miles of range into the Model S in less than 30 minutes from one of Tesla’s Supercharger stations. Tesla says there are 1,043 Supercharger Stations equipped with 7,496 Supercharges across North America. A full hour is about the equivalent of a fill up. The parking deck at my hotel had ample charging stations, so my earlier worry about range had been for nothing. I plugged the car in (it feels weird to even type that) and went to bed. I woke up the next morning to a full range of 320 miles. When you take the key out of the car’s range, it powers itself down. There’s no risk of leaving something on. The car recognizes that you’re done with its services and it handles everything else.

To experience this kind of technology first hand was eye-opening. I’m a believer in the electrification of trucking, and I’ve been selling that angle for years. When many pointed to autonomy as “the next big thing,” I pointed to electrification because I think autonomy needs it to reach its full potential. Computers best communicate with other computers, not a snake’s nest of mechanical gears and actuators.

None of this technology is conceptual or experimental. The Model S and Model 3 are production vehicles and their technologies are absolutely viable in trucking; the on-demand torque, the electrification, the automation, the customization. It works, it’s seamless, it’s comfortable and it’s awesome.

There are many important players in this space, and Tesla is simply the newest entrant as of Thursday. The work they are doing, combined with the work of Daimler, Navistar, Cummins and many others, will play a role in getting this industry where I think it is slowly heading.