Strong evidence for the ongoing microchip shortage hits hardest at dealerships where the continual absence of new cars and trucks presents a haunting scene of a third-world country.

“It’s a mess,” Ram CEO Mike Koval told Commercial Carrier Journal.

And it’s frustrating too for OEMs, fleets and consumers alike who were already in a historic holding pattern for these tiny components when Russia invaded Ukraine, a major supplier of neon gas used in semiconductor production. Russia, now a pariah nation that’s effectively cut off from the West, is a major supplier of palladium, another key element in chip production.

When asked about the impact of Russian-induced geopolitical tensions on the chip market, Koval didn’t blink.

“That’s making it worse,” he said.

Though semiconductor manufacturers reported stockpiling chip-making supplies before war broke out in Ukraine, those reserves are limited to roughly six months. Shifting to other supply sources can be tricky particularly when they’re allied with Russia.

“As significant amounts of Ukrainian production have been destroyed, other supply regions have to step in. This means China at the moment,” said Mark Thirsk, managing partner at Linx Consulting Group, an electronic materials research and consulting firm in Massachusetts. “We will see if supply continuity can be maintained, but the market for materials such as neon will be difficult in the second half of this year and may slow some chip production."

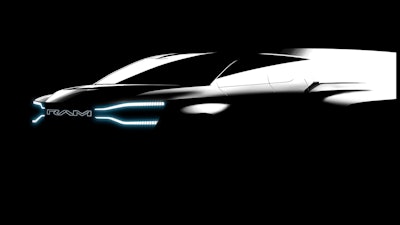

Ram CEO Mike Koval pointed out that it's not just a chip shortage that manufacturers are up against, it's also soaring prices for critical materials like steel and even nickel used in EV battery production that continue to squeeze OEMs. Artist's rendering of the all-electric Ram 1500 is shown above.Ram

Ram CEO Mike Koval pointed out that it's not just a chip shortage that manufacturers are up against, it's also soaring prices for critical materials like steel and even nickel used in EV battery production that continue to squeeze OEMs. Artist's rendering of the all-electric Ram 1500 is shown above.Ram

“The overall number of semiconductors in the automobile continues to grow,” said Andre Tauber, head of corporate media relations at Infineon Technologies AG, a major chip supplier to the auto industry.

“We expect an average growth rate of 6% to 8% annually for the semiconductor content in the automobile,” Tauber continued. “This is not only because of further automotive functions such as driver assistance systems, networking, lighting technologies and comfort and convenience applications, but also because electromobility and the electrification of hydraulic-mechanical components such as oil and water pumps or window mechanisms are also increasing semiconductor content.”

Chip demand in trucks and buses is anticipated to be even higher.

“As to trucks and buses, we expect a semiconductor compound average growth rate (CAGR) of 9% to 10% over the next five years,” Tauber added. "But please bear in mind the currently very dynamic global situation that may impact market development."

Thirsk also predicts chip use will rise.

“Demand for chips is growing quickly, and 2019 supply is too little for 2022 or 2023,” Thirsk said. “This means we will probably have supply imbalances for the next 12 to 18 months.”

GM, which will be rolling out more all-electric vehicles, including a battery-powered Silverado, plans to step up its chip orders like other OEMs.

“We see our semiconductor requirements more than doubling over the next several years as vehicles become technology platforms,” said GM spokesperson Anisha Sredzinski.

Pressures on chip production has iSeeCars Executive Analyst Karl Brauer seeing dealer lots struggling to rebuild inventories for up to two years.

“We anticipate that it will take 12 to 24 months for inventory to return to pre-pandemic levels,” Brauer said. “Once production is normalized, there will still be a backlog of consumers who have waited to buy a new car, which means that demand will continue to outpace supply.”

Hope on the horizon

Shortly after Navistar celebrated the opening of its new 2-million-square-foot plant in San Antonio, Texas, reporters had a chance to talk with company executives.When the topic of the chip shortage came up, Navistar Executive Vice President Mark Hernandez was optimistic about new chip technology and how it could help allay current chip supply concerns.

To help address chip-hungry vehicle manufacturing, including all-electric, GM is turning to advanced microprocessors that require fewer chips. All-electric 2024 Chevy Silverado WT is shown above.Chevrolet

To help address chip-hungry vehicle manufacturing, including all-electric, GM is turning to advanced microprocessors that require fewer chips. All-electric 2024 Chevy Silverado WT is shown above.Chevrolet

Michael Grahe, Navistar’s executive vice president of Operations, elaborated further on the company’s plan to use more advanced chips in microcontrollers.

“Navistar is constantly investigating new technologies which support our customers with suitable products,” Grahe said. “This also includes the usage of microcontrollers which will be introduced at a suitable time, balancing performance, quality and cost.”

GM is also feeling upbeat in its semiconductor outlook since, like Navistar, it’s shifting away from old chip technology.

“GM’s new strategy will reduce the number of unique microcontroller units (MCUs) required by 95% to industry-leading levels, which will help drive quality and greater predictability and resiliency throughout the supply chain,” Sredzinski said.

“We estimate one new microprocessor family alone could account for more than 10 million units annually,” Sredzinski continued. “We expect much of the investment needed will flow to the U.S. and Canada. The three core microcontrollers are designed to provide more than seven years of platform stability, unlocking software developers to focus on creation of high-value, customer-facing feature content.”

Infineon has been working with auto manufacturers, including GM, to help build more efficient systems.

“Manufacturers are working on reducing the complexity of the car system,” Tauber said. “Currently, a car has 80 to 100 control units, and trucks/buses have about 50 control units, which is already very complex. In the future, there will be central computers for the driving calculations as well as some zone computers. However, separate electronic systems will remain for basic driving functions such as brakes, electronic steering or airbags.”

Challenges ahead

Changes in manufacturing are something that come slowly for the auto industry. Navistar is banking on new chip technology to help restore supply chain resiliency. All-electric eMV is shown above.Navistar

Navistar is banking on new chip technology to help restore supply chain resiliency. All-electric eMV is shown above.Navistar

“[For example] a central electrical bus that runs electronics and power would be cheaper, lighter and offer future proofing but is difficult to implement across the industry with multiple proprietary standards,” Thirsk continued. “I know cars want to go this way, and the CANBus is an example of this.”

Switching to new technology takes time and plenty of investment.

“I doubt new manufacturing capacity or new technology will offset inventory problems of currently used chips,” Thirsk said. “Automotive chip suppliers operate out of older factories (fabs), and although some investment is occurring (Bosch in Germany; Renasas in Japan) and chip production is at very high levels (+17% last year), the hole created by the automakers switching demand off and then on in 2020 is fighting for capacity with high demand in other markets.”

It's not only that. As Koval pointed out, it’s also rising prices in nickel for EV battery production, steel and other materials that’s making vehicle manufacturing more challenging.

“The whole situation is horrible,” Koval said. “We are absolutely in an inflationary state, and it’s making things challenging. Everything — the price of steel, precious metals — are all going through the roof. So, like everybody else, we’re managing it the best we can and try to stay out in front of it as much as possible. But this chip situation is a mess.”