Suppose someone came to you today and said they could solve a huge problem you don’t even know you have.

Would you listen to them, or shoo them away?

They would start the conversation with all you need do is inject massive amounts of capital, revise decades of regulations, rewrite labor contracts and convince both the industry and the public that the new solution is better than what you already have.

There are days when I feel the push toward automated trucking is like that.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m a technologist. Automating trucking has a lot of intriguing technological aspects. It checks the box for the “cool” factor.

But what exactly is the problem automated trucking is supposed to solve?

The driver shortage, right?

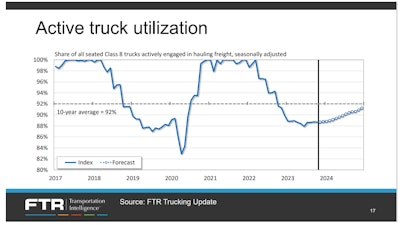

What if we’re not in a driver shortage? FTR’s Avery Vise reports active truck utilizations and, if I’m not mistaken, there is more freight capacity than there is demand for freight. The graph shows there are times where demand exceeds capacity and others where the reverse is true. Let’s talk that out a bit.

What do all those future autonomous truck drivers do in the freight trough when capacity exceeds demand? Do they change jobs and go haul refuse? Do they change regions and try to find some part of the world where trucks are in demand? Or do the trucks get parked on the fence? Do they get sold into the depressed used truck market? Does all that capital invested in automation suddenly get stranded waiting for the next freight demand up cycle?

Do those parked trucks at your fence need care and feeding while they are grazing at the back fence? Do millions of lines of software code need regular updating? Do the sensors need to be checked? Will the wires need to be checked to avoid rodent damage? What about hail risk? Will you be able to shut the power off entirely to the truck while it sleeps or will it sit there continuously draining batteries?

Replacing your operating expenses with capital expenses is typical justification for putting robots into manufacturing centers. Paint robots, welding robots, etc., are all rationalized (in part or entirely) on replacing human labor expense with capital cost. What is often forgotten in that substitution is that computers require maintenance, and software licenses have continuous maintenance costs.

The rush toward automation in trucking is entirely about replacing humans with machines. Face it: Drivers are a real problem in the industry. Really. They have to be paid a competitive wage. They hire in, then quit and go somewhere else when there is more money or better working conditions. They even leave to start their own competitor companies. They are human and make mistakes. They have all those rules tied to being human like hours-of-service regulations and OSHA standards. They have benefit packages that need funding. They have worker’s compensation. Hiring them takes time and money. Often you have to train them. Drivers are a lot of paperwork. Seriously, who really needs drivers? At least that’s the view of hopeful AV investors.

Machines, on the other hand, do what you tell them to. They don’t quit. They don’t have worker’s compensation claims. They don’t make mistakes. They don’t require benefits packages. They don’t have to be home at night to see their families. They never get sick. They don’t get into accidents and never get sued or go to court. They are perfect. Really. Or that’s what we are hoping.

If you’ve made it this far, please read on

However, not all things autonomous result in savings. Keep this in mind, especially if you’re drinking that computerized Kool Aid. Software maintenance costs are now engrained as the primary means that technology companies have for achieving annual cash flow.

Some of the older people in the room may remember when you could buy a perpetual software license and never have to write another check to the software company. When was the last time anyone gave you a perpetual software license? You now have annual subscriptions subject to inflation and profiteering because you are a captive customer. And get ready for mandatory hardware upgrades when the next version of software comes out and its not compatible with your older equipment.

A lesson learned from aerospace is that having a fleet of vehicles all connected to a software company means that software can bring your entire fleet to a standstill with any number of events. Consider that in your risk mitigation strategy. One bad truck may mean an entire fleet of bad trucks needing to be immediately fixed before they roll on. Sure, over-the-air updates will be engaged, but what if the problem takes more than a moment to figure out and fix? Can you afford to have a large portion of your trucks down all at the same time waiting for a software engineer to troubleshoot the problem and certify a fix?

Recalls have become quite common with trucks, usually tied to mechanical defects. Sometimes these are serious enough to force fleets to stop using their trucks, but usually they are handled as time permits based on what the driver and fleet feel is appropriate. Will you trust your autonomous “truck driver” with that decision? What will your lawyers advise?

I asked fleets how long it takes put chains on a truck and trailer. Some told me an experienced driver can do it in “a few minutes” but an inexperienced one can take some time. Who is putting chains on your autonomous truck? Or will you choose not to run the truck in winter? Will you keep a pool of human drivers on speed dial? How will you pay them to be ready for that call?

At a TMC meeting, an FMCSA representative pointed out one of the more obvious questions: Are automated tractors pulling legacy “dumb” trailers safe? How does the tractor know anything about the trailer? How does the tractor see behind the trailer? Who is responsible for the safety of the trailer?

The autonomous trucking industry talks about edge cases as if they are rare events. In reality, there are a lot of edges. Fog, animal impacts, sandstorms, snowstorms, high water, floods, ladders flying across the highway, road gators, flat tires, emergency vehicles, roadside fires, vehicle fires, unpredictable people in nearby vehicles — driving is experiential. That is why 1,000,000 mile safe truck drivers are celebrated and valued by fleets versus inexperienced newbies.

Advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) are potentially great additions to trucks and trailers to help make driving safer for drivers, but they add capital and expense to the truck that may only be offset by taking cost out elsewhere. Where is that elsewhere? Remove the driver? However sincere the claim that automation will not eliminate human drivers, the reality is economics require paying for automation by not paying a driver.

The camel’s nose under the tent is justifying replacing drivers on long, physically taxing routes with autonomous tireless “drivers.” Aren’t those the routes with the greatest earnings for drivers? Taking drivers out of long haul inherently means putting them in short haul. What does that do to a driver’s earnings? Most urban and short/regional haul is under 150 miles per day. For drivers paid mostly by the mile, that is a big hit versus 400 to more than 600 miles per day.

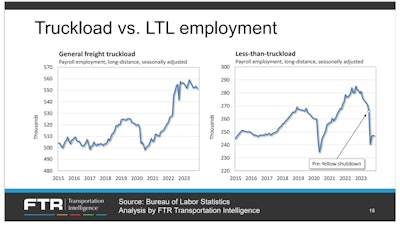

Did the driver’s ask to be replaced by autonomous vehicles? I don’t have statistically significant survey answers for that, but I suspect most truck drivers understand they drive for a living, or they would be doing something else. Is there a shortage of drivers? Researchers like those from the American Transportation Institute have reported for decades that there is a driver shortage. Who am I to argue? Let’s look at FTR’s data that shows the industry absorbed significant demand changes in 2022-2023 before the market fell off. Where did those employees come from? How does the industry constantly deal with peaks and valleys in freight demand? It seems like there are drivers out there when needed.

One significant reason to promote autonomous trucks is that they never get tired, they don’t have hours-of-service limitations. You can run them 24/7. Really? What often is not discussed is that running a truck 24/7 means it wears out faster in terms of calendar time. You will hit your warranty mileage limit before the calendar limit. Wear items like tires and brakes will need to be dealt with more often as autonomous trucks rack up two to three times the miles per day that your trucks have been seeing. Your capital replacement cycle of trucks likely will have to shorten.

And what about all those support people at your maintenance facilities, distribution centers and such that used to go home at night? Aren’t there 24/7 ramifications to those assets? Even your customers may need to provide 24/7 assistance to receive loads at all hours of the day. Who pays for that coverage? Oh, I know, those will all be automated, too.

Fleets may want automation, or think they do, on the assumption that computers will be easier and less costly to deal with over time. Good luck with that.

If you are considering autonomous trucks as the solution to your driver challenges, ask yourself what your IT budget and staffing has done in the last couple of decades. How has software related downtime impacted your trucks?

Be careful what you ask for, you might actually get it.