I had a class in college that required me to research communications. Communication was a lot simpler then: no internet, no email, no cell phones, no laptop computers. Post-it boards actually used physical paper notes secured with thumbtacks. There was no such thing as PowerPoint, no Gmail, no X (formerly known as Twitter). Yes, the Dark Ages.

Phones were still tied to the wall with four wires. My parents still had a rotary dial phone, and I knew how to use it. AT&T had not been broken up yet, so still held a monopoly on telephony in the U.S. Conference calls were expensive and largely reserved for executives.

Television had expanded into cable systems, but I still had a rabbit ear antenna TV that picked up all of four stations. News came to me via accepted reliable industry icons from CBS, ABC, NBC and PBS such as Walter Cronkite, David Brinkley, Frank Reynolds, Harry Reasoner, John Chancellor, Roger Mudd, Robert McNeil and Jim Lehrer. You got your national information from a handful of vetted television news stations, and local news from your local station that actually employed local reporters. Politicians had to get their message into soundbites on the evening news reports, competing for time between advertisers, sports, weather and public interest stories in that critical evening half-hour time slot.

Thick daily newspapers were essential to information searches. Paperboys and girls were still delivering them to houses off their bicycles or on foot, but that news was still at best a day old. Magazines were glossy, thick, ubiquitous, and, at best, weekly, like Newsweek and TIME.

I’m a realist, not a nostalgic Baby Boomer. How we communicated in 1978 was much simpler than today, but not better. Demographics were also grossly oversimplified, compositing large diverse groups into stereotyped large categories.

My college report focused on the fundamentals of communication; that communication requires a sender, a receiver and a message. Picture Alexander Graham Bell and his first phone call to Watson. Both the sender and the receiver have their own unique understanding of language, words, accents, emphasis, idioms and such.

Definitions are in the ear of the listener. There is no guarantee, for example, that the word “transmission” means the same to both parties. If you are an engineer working at Eaton talking with a utility engineer working at the Bonneville Power Administration, it’s very likely that the word transmission has two completely different meanings.

Successfully communicating means that the intended message and the received message are consistent. A habit of successful presenters is to have the receiver restate what they have heard in their own words to confirm the intended message was accurately interpreted. Successful communications require some effort.

Scale is perhaps one of the most complicated aspects of messaging. What you understand as big may be small to your receiver. You both are nodding in agreement, but the picture in your head is entirely different than the one in your receiver’s. An example of this is expressing greenhouse gas emissions savings in tons of CO2, a measurement not most people can visualize or comprehend. Or picture a conversation about gross national product between someone from the U.S. Federal Reserve and someone from the government of the Bahamas. The Gross National Product (GNP) of the U.S. weighs in at more than $25,000 billion while the Bahamas’ GNP tips the scale at roughly $13 billion.

I helped develop a truck instrument gauge package years ago. I was in my 30s and still had pretty good vision. The executives and senior engineering experts reviewing the alternatives were generally older. What I thought was reasonably legible in terms of font size was different from what they did.

Color also became a key topic. I did significant research on color blindness and found that more than 10% of people have some variation of color blindness: one in 10 people. Later in my life, one of my sons was one of those people impacted by color blindness. What is “green” to one, may have multiple interpretations to others, and some may not see it at all. I have become an advocate for describing colors using clearly defined wavelengths, something modern physics has provided, and is the basis of the nifty color matching spectrophotometer machine in the paint department of your local hardware chain.

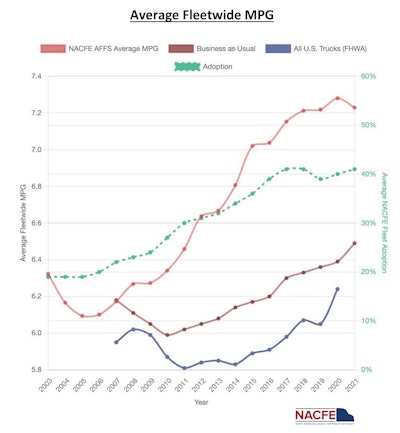

Specificity is important in getting your message correctly interpreted. Words like large, big, a lot, faster, slower, etc. are all pretty useless unless pegged to a numbered scale. Great fuel economy improvements expressed in percent are also fairly useless. A 10% improvement in mpg for a truck averaging 6 mpg is 0.6 mpg, while a 10% gain for a truck averaging 10 mpg is a 0.1 mpg gain, almost immeasurable in repeatable real-world road testing. Without a basis, the percents are just arm waving. A CEO I once worked for was adamant that expressing percents always had to be combined with stating the hard physical numbers upon which the percents were based.

Which brings me to stating the electricity requirements of battery electric trucks in terms of the number of houses the same energy could power. The fundamental purpose of this visual is to quickly convey energy use in physical terms people can understand. Only this comparison never mentions how many houses the equivalent diesel engine could power if it were running a generator.

Turns out that the diesel in that truck could power an electric generator that could power a large number of homes. Because the energy conversion efficiency of the combustion engine is worse than that of battery electric power, it also means the battery electric power wastes significantly less energy than the diesel. Think of this in terms of a battery electric truck vs an equivalent diesel truck, expressed in equivalent number of houses powered — the BEV could power two or three times as many houses. This is the positive aspect of comparing BEVs to diesels in terms of house energy use.

Successful communication starts with understanding terminology. Comparing BEV energy use in terms of number of homes it could power can be useful, but only if the equivalent comparison is made for diesels.

The discussion of BEV energy use in housing equivalency erroneously infers that somehow BEVs are going to cause blackouts for homes.

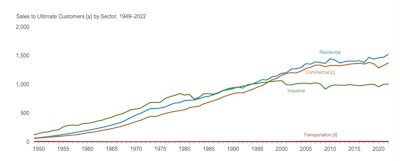

BEVs are just another utility load, and the utility industry needs to provide generation capacity and distribution to assure reliable energy delivery to all users. As society and industry migrates to greater use of electricity versus traditional fossil fuel power, demand growth is a reality. Capital investment in both generation and distribution, along with improvements in efficient use of energy, are the keys to handling this growth.

In the 1950s, everyone had to have electrically powered refrigerators, then air conditioners, and so on. Load growth occurred and the utilities responded with increased generation and transmission capacity. BEVs are just another new load for utilities to address. Electrical load growth is nothing new. The industry has been handling this trend for decades as expressed in billion-kilowatt-hours by the U.S. Department of Energy in this graph.

Reliability is a priority for all 3,000-plus U.S. utilities. The U.S. grid has been described as the largest machine in the world. One of the reasons for lengthy installation times for getting power to electric truck depots is that the utilities have to ensure the new loads will not reduce reliability for all users, not just those getting trucks.

Effective communication is the key. Responding to new load growth is where efforts such as EPRI’s EVsToScale2030 and DOE’s EVs@Scale programs are valuable bringing utility experts and transportation leaders together to successfully communicate and coordinate solutions to handling future transportation electrical loads.