Members of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) went on strike just after midnight Tuesday at three dozen facilities across 14 port authorities stretching from Maine to Texas. More than 40% of all U.S. imports flow through the East and Gulf Coast.

The work stoppage at all the Atlantic and Gulf coast ports halts the processing of tons of goods daily from consumer electronics and appliances to furniture, beer, produce and many items in between.

"Consumers may be especially interested in seeing the impact on coffee, finished motor vehicles, fruit and vegetable juices, wine, bananas, other fresh fruits, and flavored beverages," noted Jason Miller, associate professor of supply chain management at Michigan State University and interim chair of the Department of Supply Chain Management. "Auto parts are the most interesting industrial import."

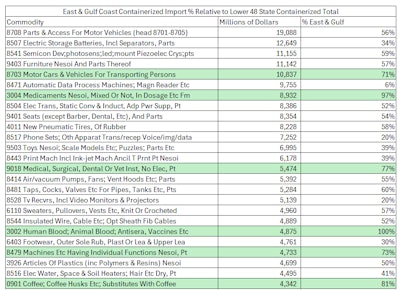

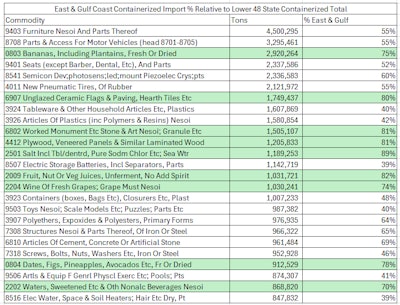

Focusing only on containerized imports, the two tables report the top containerized imports across all lower 48 states (West, East, and Gulf Coast ports) by dollar value (top) and tonnage (bottom) and then report the percentage of containerized imports that enter through the East and Gulf Coast ports. Data are year-to-date through July. Goods where the East & Gulf Coast total exceeds 70% are highlighted in green.Jason Miller, Michigan State University

Focusing only on containerized imports, the two tables report the top containerized imports across all lower 48 states (West, East, and Gulf Coast ports) by dollar value (top) and tonnage (bottom) and then report the percentage of containerized imports that enter through the East and Gulf Coast ports. Data are year-to-date through July. Goods where the East & Gulf Coast total exceeds 70% are highlighted in green.Jason Miller, Michigan State University

President Joe Biden said he will not intervene despite calls from numerous groups, including the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), to invoke the Taft-Hartley Act, which would force ports to resume operations while negotiations continue.

“There will be dire economic consequences on the manufacturing supply chain if a strike occurs for even a brief period," said NAM President and CEO Jay Timmons, whose organization estimates the strike jeopardizes $2.1 billion in trade daily, and the total economic damage could reduce GDP by as much as $5 billion per day.

Timing of a strike could not have been worse, kicking off just days after a major hurricane wrecked much of the infrastructure from North Carolina to Florida, and as signals showed that much of the supply chain snarl that had plagued the last three-plus years had loosened.

"By and large, other than this threat of a port strike, supply chain glitches have largely resolved themselves, with data from both the Census Bureau and Eurostat showing the percentage of manufacturers citing raw material shortages as affecting their capacity utilization has fallen back to pre-COVID levels," Miller said.

The largest longshoremen’s union in North America is warring with United States Maritime Alliance (USMX) over higher wages and a ban on automation technologies that guide cranes, gates and the movement of containers. USMX filed an “unfair labor practice” charge against the ILA as talks broke down last week.

“In the short term, we’d expect minimal impact on supply chains as shippers anticipated a strike and front-loaded imports earlier in the year," said Dean Croke, DAT Freight & Analytics principal analyst. "A prolonged strike — longer than a week — would be more disruptive but could create opportunities for carriers on the spot market. Freight diverted to ports in eastern and Atlantic Canada — Halifax, Saint John, Ottawa and Montreal — would need to be trucked into the United States. Demand for air would surge to move high-value and late-season goods like electronics and pharmaceuticals, which would need to move by truck out of air cargo hubs."

FTR CEO Jonathan Starks agreed that shippers have had ample time to prepare for the port strike, adding there had been a surge of imported containers during the late summer months, "so inventory should be available and accessible," he said. "Our assumption is a two week strike, which is long enough to create some pain in the transport markets, but not long enough to create significant pain for the consumer or the industrial supplier."

Anything that encroaches late into the month and nears the presidential election date, Starks said, would start to change that equation, "and shippers would begin to make more significant changes to their shipping patterns as intermodal facilities could start to max out."

One thing an extended strike could bring is an emergence of severe lane imbalance, Croke added. For instance, Canadian lumber will be in high demand for rebuilding in the Southeast on the heels of Hurricane Helene. "But loads of machinery, steel, and other equipment that flatbed carriers would move from Baltimore back to Canada would dry up," he said. "It’s something to watch."

Spot load posts for all three equipment types increased across the Southeast last week as shippers staged freight or moved inventory to safer locations ahead of the storm, Croke said. This week, road closures, power outages, and delays in getting fuel from racks to gas stations make it hard for anything to move. This should change next week once roads become passable and power is restored and Croke said, in the coming months, recovery from Helene will be more of a story for flatbed carriers. "They’re essential to moving construction materials, machinery, and heavy equipment needed to rebuild," he said.

Holiday shopping implications

Jason Miller, Michigan State University

Jason Miller, Michigan State University

Another case of poor timing is that shelf-stocking for the holiday season is about to kick off in earnest, and while the direct impact a port strike can only be guessed right now, historical data suggests a merry Christmas still lies ahead... for the most part.

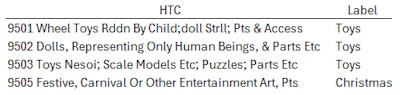

"We can see a very clear pattern in that 2022 – a year with chronic port congestion – saw toy imports primarily arrive in August and September, as opposed to October as occurred in 2017 and 2023 when the ports were operating smoothly," Miller said.

This year is closely following the pattern from 2022, according to Miller, suggesting front-loading of these imports.

"Consequently, I do not believe Americans have much to fear about holiday goods being available. The concern is much more for goods that can't be front-loaded, such as auto parts or perishable fruits," he said. "Likewise, U.S. exports such as paper, frozen meat, motor vehicles, and plastic resins can't be front-loaded, and thus a prolonged strike could affect domestic U.S. manufacturing output by reducing demand because exporting is precluded, in addition to a prolonged strike causing plants to slow production because imported inputs can't be obtained."

Miller added that an extended East and Gulf Coast port strike wouldn't spark widespread shortages of foods and beverages. While imported fruits and alcohol could become more challenging to find, he said, there is no concern about running out of meat, milk, bread, or other food staples – products that are produced almost entirely in the U.S.