After you have worked on a few new truck designs, you start seeing a pattern – a relationship between the pieces. Eventually you grasp why trucks are the way they are, and how hard it is to change their shape.

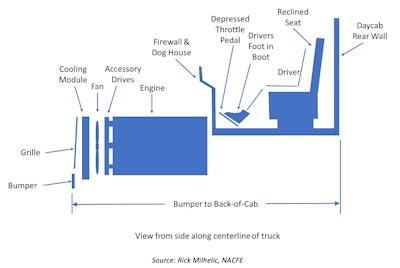

Let’s start along the centerline of a narrow cab on an older traditional cab-behind-engine diesel truck, starting with the engine — the heart of the truck. A diesel engine has a particular size and shape. In front of the engine are belt-driven accessories. One of those is a very important fan blade. The fan blade has to have room to spin, and enough clearance to help move air around and out of the engine cavity. In front of the fan blade is the all-important cooling module, which needs both thickness and surface area to work effectively.

In front of the fan is the grille – the front end of the truck and arguably one of the brand identifiers. The grille originally was vertical but over the years aerodynamics designs and styling have required it to be tilted back a few degrees to help reduce drag. The grille generally is slightly behind the face of the bumper, so that the bumper is the first thing to hit any obstruction.

Behind the engine block is the firewall. Some clearance needs to be provided between the engine and the firewall because they move differently. The firewall is where nearly everything is located that has to transit into or out of the cab, such as signals to gauges in the instrument panel, air lines, electrical harnesses, air conditioning air, etc. Directly behind the firewall, and directly opposite the left rear corner of the engine block, is the throttle pedal (and the driver’s foot).

Like the old childhood song, "the foot bone is connected to the..." You wind up needing to position the driver’s body in a seat so that the ergonomics — the driver’s comfort — are appropriate for all size and shape of drivers, which includes 5% to 95% of the population.

The seat is slid back to fit the 95% percentile driver. The seat has to have some ability to recline, unlike that airline seat in the exit row of airplanes, so the back of the cab – with its interior trim package – has to be located beyond the seat recline position chosen for the vehicle.

The bumper-to-back-of-cab dimension is also critical to fleets. The market values shorter bumper-to-back of cab dimensions, so the outside of the back wall has a constraint as well. This means that all the gaps between elements are decreased to their bare functional minimums.

Modern truck cabs are wider than older traditional cabs. This was done by increasing space between the seats so it’s easier to get into and out of the sleeper versions of these trucks. They also are wider to help with aerodynamics and styling. As the seats moved outboard so did the throttle pedal, eventually getting to the side of the engine rather than behind it. But that only bought a little bit of room for designers. The basic geometry constraints were all still there.

Over the years, designers came up with creative ways of getting a little extra room by extending the cab rear window space. This allowed seats to recline further while technically not increasing the bumper-to-back-of-cab dimension. Another alternative to this diesel packaging arrangement is the cab-over-engine, where the whole cab is raised and positioned over the engine. When given a market choice in the 1980s and 1990s, the market shifted away from cabovers for diesel powered trucks. Some of the new entrants for zero emission vehicles and hybrids seem to be bringing the cabover back to the market.

In this brief space, I’ve outlined why cab-behind-engine diesel trucks are shaped the way they are, and how few geometry decisions are really open for debate by the engineers. In the process of designing new trucks high-fidelity computer aided design models are built, and different engineering groups, suppliers and styling groups argue over millimeters, and the pluses and minuses of tolerances become critical.

Let's now introduce battery electric drivetrains into this problem. The elimination of the diesel engine block from the geometry means everything from the firewall to the grille is fair space to completely reconfigure the shape of the vehicle. The human body, throttle pedal, the driver’s seat and the interior of the cab are still requirements, as is the bumper-to-back-of-cab requirement. But everything under the hood can be configured in many different ways. This opens up the possibility of completely reshaping the front of the vehicle.

Now, let's introduce an autonomous vehicle, or automated and connected vehicle if you prefer the correct terminology. The human body, throttle pedal and the driver’s seat are no longer a requirement. In fact, having any interior space is not really a requirement at all.

We are on the cusp of radically re-envisioning freight-carrying trucks. Zero emission vehicles without combustion engines and autonomous vehicles will combine to make future trucks look completely different than what we have grown used to. Many OEMs and suppliers today seem caught up in trying to make future trucks look like today’s diesels. That is based on trying to gradually transition to the new technology by making it familiar to the buyers, but that does not take advantage of all the benefits of new technologies.

In my dealings with visionary industrial design teams, a sage bit of advice was that customers don’t really know what they want until they see it. Pushing us out of the status quo is what new technologies are intended to do. If a 2050 model year semi-truck looks like a 2020 model year one, we will have failed to make the most of the new technologies.

Rick Mihelic is NACFE’s Director of Emerging Technologies. He has authored for NACFE four Guidance Reports on electric and alternative fuel medium- and heavy-duty trucks and several Confidence Reports on Determining Efficiency, Tractor and Trailer Aerodynamics, Two Truck Platooning, and authored special studies on Regional Haul, Defining Production and Intentional Pairing of tractor trailers.