Buck Shepherd and his golden retriever, Bubba, are now retired from trucking.

Buck Shepherd and his golden retriever, Bubba, are now retired from trucking.Last March, 67-year-old Buck Shepherd was delivering windmills in Oklahoma as an independent operator leased to Sycamore Specialized Carriers in Ft. Wayne, Ind.

“The nicest company you could work for,” he says. Beginning next year he planned to ease into retirement by working part time until the age of 70.

Unexpectedly, he started to feel tightening in his chest with difficulty breathing. The problem grew worse. In May he returned home to South Bend, Ind., to see a doctor.

The initial diagnosis was pneumonia with a blood clot in his lungs. Further testing revealed three clogged arteries and a serious heart condition.

On Sept. 8, doctors put stents in his arteries and a defibrillator and pacemaker in his chest. From that point on, Shepherd was high risk for another heart attack.

“Unfortunately, my driving career is over,” he says.

By outward appearances Shepherd is physically fit, but the stress of his job and his erratic work schedule, he believes, were factors in his deteriorating health.

Truck drivers “probably don’t take care of ourselves and do not get medical attention like we should,” he says. “When I went on a job, I stayed with the job until it was done.”

More than half of truck operators in the United States are now 45 or older. Labor shortages caused by an aging workforce are now compounded by health risks for drivers of all ages.

A 2014 study by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration found that 69 percent of drivers were obese; 54 percent smoked; and 88 percent reported having at least one risk factor — hypertension, smoking, obesity — for chronic disease compared to 54 percent of U.S. workers.

A call to action

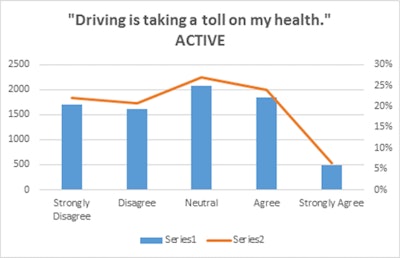

Stay Metrics research found that 30 percent of drivers believe their career is adversely impacting their health

Stay Metrics research found that 30 percent of drivers believe their career is adversely impacting their healthThirty percent of drivers feel that their career is taking a toll on their health, according to survey data collected by Stay Metrics from nearly 8,500 drivers over a three-year period. With irregular work schedules and extended periods of isolation and inactivity, drivers face an uphill battle for staying mentally and physically fit.

Stay Metrics provides research to clients in the trucking industry to determine the root causes of driver turnover. To date, the research shows that drivers are not changing jobs or leaving the industry because of health concerns.

One explanation is that drivers who are already in poor health may feel they have no other option than to keep driving, says Tim Hindes, the company’s chief executive officer. Another possibility is that 70 percent of drivers are somewhat naïve about the health risks of the profession.

“This should serve as a wakeup call for the trucking industry to provide more wellness training and related services to drivers,” he says.

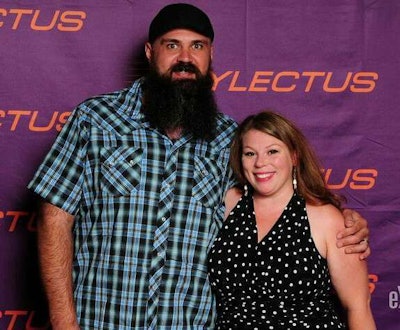

Some drivers are defying the odds. Nick and Jennifer Marcu, age 34 and 31 respectively, have been on the road together since 2009 as an owner-operator team leased to FedEx Custom Critical.

Nick lost over 125 pounds since Jennifer joined him on the road. She is 75 pounds lighter. The turnaround has been possible by cooking three healthy meals each day. She also makes sure they both get a moderate amount of daily exercise.

Mental well-being, she says, is also essential for physical health. Keeping a journal, for instance, helped her correlate unhealthy eating habits with an emotional need. Identifying the source of that need made it possible to respond in a different way than eating. For many drivers, loneliness also causes unhealthy habits, she believes.

Owner operators Nick and Jennifer Marcu have lost a combined 200 pounds by changing their lifestyle.

Owner operators Nick and Jennifer Marcu have lost a combined 200 pounds by changing their lifestyle.Self-motivated drivers like the Marcus are within the ranks of fleets, but most need help to choose and sustain a healthier lifestyle. With skyrocketing health care and workers compensation costs, companies are looking for more effective ways to intervene early on.

“We are aggressively looking at health and wellness methods to reduce exposure and cost,” says Chris Cooper, president of Boyd Bros. Transportation, a flatbed carrier based in Clayton, Ala., with 1,200 power units. “But we are mainly doing it to extend peoples’ lives.”

Leveraging technology

Corporate health and wellness programs come in many shapes and sizes. A program that works for one may not be effective for another.

Chris Cooper, left, says that driver health and wellness is one of the top issues for Boyd Bros. Transportation

Chris Cooper, left, says that driver health and wellness is one of the top issues for Boyd Bros. TransportationBoyd Bros. is considering personal health coaches for drivers administered by a third party, Cooper says. Other strategies implemented by fleets include onsite fitness centers and health clinics. Some are sending nutrition boxes to drivers to encourage better eating habits on the road.

An increasingly common, and effective method, is the use of technology to heighten awareness, provide training and engage drivers in health and wellness programs.

Stay Metrics has partnered with Mopi16, an expert in adult learning, to provide a free Wellness Training Module that is accessed by drivers through the online recognition platform Stay Metrics administers for clients in the transportation industry.

Kurt LaDow, co-founder of Stay Metrics, says the module includes a series of monthly training videos that provide a basic education on healthy lifestyle choices that deliver immediate benefits.

Each of the short training modules incorporate gaming, animation, rewards, feedback and assessment of learning outcomes. Drivers earn points for completing the modules and taking quizzes. Stay Metrics’ online recognition and rewards platform has a leaderboard that shows drivers how they rank among their peers in terms of points earned in various categories set by their fleets.

Drivers redeem their rewards points from an online catalog with thousands of consumer items.

A holistic approach

Increasingly, transportation companies are working with health care providers to get a complete risk assessment of their employees. This process starts with biometric screening to establish a baseline for current and future health risks.

Celadon Trucking has a full-size gym, weight room and on-site health care clinic at its Indiannapolis headquarters. Photo by Marty Moran

Celadon Trucking has a full-size gym, weight room and on-site health care clinic at its Indiannapolis headquarters. Photo by Marty MoranBiometric screening can be more difficult in transportation due to mobile workforces, but more health care providers now have a nationwide network of clinics, says Nicole Fallowfield, director of health management for Gibson Insurance, a full-service risk management consulting firm based in South Bend, Ind.

Wellness vendors that conduct biometric screening typically manage employee health data and consult directly with drivers, she says. And some also have mobile apps that give drivers access to personal records and tools to track their progress.

Wearable devices like the Fitbit can also be effective. The technology connects people with friends, family and colleagues to engage in health competitions and to monitor progress towards goals for calorie intake and other health metrics, she adds.

Ultimately, the reason people decide to improve their health may not come directly from an employer’s wellness program, Fallowfield says. Other factors, like job stability, income and company culture contribute to an individual’s overall sense of well-being.

“You probably have a better chance by making the workplace a good place to be, or even showing that leadership and management truly care,” she says. “You can’t get somebody to change, but you can provide the conditions that make it easier to make a healthy choice.”

Since drivers must be examined by a certified physician every two years to maintain a CDL, awareness of chronic diseases like sleep apnea, diabetes and hypertension may not be the problem. Instead, what many lack is the help, support and education needed to achieve desired results.

Buck Shepherd believes his condition may not have been preventable, but “there were signs” that he ignored. “The biggest problem is that we don’t listen to our bodies,” he says. The fact he is still alive is another type of sign.

“Not everybody believes in God, but I believe there was more than just myself and my dog in that truck when I left Oklahoma.”