Note: This is the third and final installment of a multi-part series on natural gas’ role in trucking. The first article, “The politics of natural gas trucks” can be found here. The second, “Clearing hurdles that aren’t diesel prices” can be found here.

However, the average price of diesel fuel fell to $2.30 per gallon last year, its lowest point since diesel crossed the $2 per gallon mark in 2004, and stunted growth in the segment.

“Diesel prices are a headwind,” Westport Fuel Systems Vice President of Business Development and Product Management Brad Douville says of adoption rates. “The [return on investment], depends on mileage and several other factors, but at $4 [for a gallon of diesel], the phones don’t stop ringing.”

“I don’t want to call it a stagnant market,” adds ACT Research Vice President Steve Tam, “but I would argue we’re in between the innovator and early adopter stage.”

The U.S. Department of Energy says the use of natural gas reduces greenhouse gas emissions from 6 to 11 percent and according to ACT Research data, 6,885 natural gas trucks were sold last year, up slightly from 6,767 units sold the year before.

Driven mostly by engine emission regulations, the agency’s forecast calls for 6,900 units this year – about 4 percent of all heavy truck sales expected for 2017.

Cheap diesel and concerns about the mileage range of natural gas engines may have kept the second wave of truck buyers out of the market, but domestic shale gas production and increasingly strict emission standards may be poised to reignite interest in alternative powertrains.

Frost & Sullivan, in a report released in February, projects market penetration of natural gas heavy-duty trucks to reach 7.2 percent by 2025.

“As the market experiences increased propane penetration rates, OEMs need to expand their engine portfolio with gasoline engines or forge partnerships with technology experts,” says Frost & Sullivan Mobility Research Analyst Saideep Sudhakar. “The entry of Nikola and Tesla in the hybrid and electric truck market and Provost and Temsa in the alternative fuel buses market, will prompt major OEMs to launch similar offerings.”

From 2011 to about 2013, when natural gas-fired engines were quickly building momentum, many foretold of adoption rates of 20 percent by 2020, but Douville says those expectations have been dialed back.

“Twenty percent by 2020 isn’t realistic,” he says. “We can get to 20 percent but on a delayed timeframe. What’s driving [adoption] is going to move from parity in the price of oil to ‘what is the price of a diesel vehicle that’s going to meet the GHG requirements?’ I think were going to see the economic equation shift, and that will drive penetration.”

Ryder, which has more than 1,000 natural gas trucks in its fleet, says low diesel prices have changed how customers are utilizing the company’s natural gas offerings and its capabilities.

“As [the gap in price between natural gas and diesel] has compressed over the past 2 years, the direct economic benefit the customer could have achieved 3, 4, or 5 years ago is dramatically different, says Ryder’s Chief Technology and Procurement Scott Perry. “The ability to offset that increased cost has diminished pretty significantly. Compared to number of vehicles we were putting into service a number of years ago, the pendulum certainly has started to swing the other way.”

Options, options, options

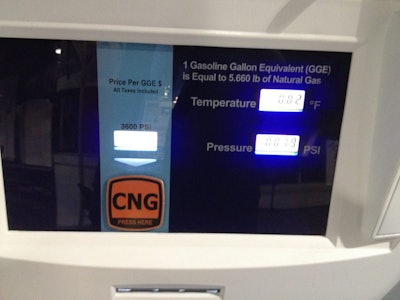

In heavy duty transportation, natural gas is pretty much a two-horse race: Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), and even in that limited field CNG has started to pull away.

“LNG has somewhat fallen out of favor in the industry,” says Tam. “The issue has been that it’s more expensive [due to dispensing] even though it kind of does address the range issue.”

Douville says CNG adoption has been aided by the fact that fleets can experiment with the fuel on a smaller scale, and with less investment, than LNG.

“You need a critical mass to open an LNG station. If it’s cold, you need about 20 trucks and if it’s warm LNG, you need about 40 trucks,” he says. “That becomes significant for these fleets who would like to step towards it rather than run towards it.”

Tam notes that no engines are currently being manufactured that require LNG, but most natural gas engines can burn it.

“The demand has spoken,” he adds.

UPS – the largest trucking fleet in the U.S. – invested $100 million last year in CNG fueling stations and plans to build six more while deploying 390 new CNG tractors and terminal trucks to its fleet.

UPS is also adding 50 LNG trucks and last year deployed 50 LNG vehicles in Indianapolis, Chicago, Earth City, Mo., and Nashville where the company has existing LNG stations.

Even with alternative fuels making up less than 5 percent of truck sales, the field of options is getting crowded.

Just last year, Nikola Motor Company (NMC) promised the launch of a hydrogen fuel cell powered Class 8 tractor – a prospect that has Tam excited.

“I tend to root for the underdog, so I want to see it be a success,” he says. “The technology works. The application of the technology is the part [NMC founder Trevor Milton] has got to figure out how to make work.”

Tam and Milton aren’t the only ones excited by the possibilities of hydrogen.

“We are defiantly drinking the hydrogen cocktail,” says Mike Britt, UPS’s global director of maintenance and engineering who notes that UPS has been working on a fuel cell product in its 22,000 pound trucks since 2010. “A hydrogen fuel cell propelling electric vehicles is the pathway to zero emissions. We really believe renewable hydrogen is the way to go.”

Hydrogen, LNG and CNG are only a small sampling of the alternative fuels running the streets in what Britt calls UPS’s “rolling laboratory.”

Last year, the company crossed the one billion mile mark using alternative fuels since 2010.

“Today, we drive more than 1 million miles globally in our alternative fuel or technology advancement fleet,” says Carlton Rose, president global fleet maintenance and engineering for UPS.

UPS has almost 1,400 LNG tractors in the U.S. and 19 biomethane tractors internationally. Almost 1,800 CNG package cars have been deployed in the U.S.

Among the fuels in use in UPS’s rolling laboratory are electric/hydraulic hybrid, electric, ethanol, LNG and CNG and biomethane, renewable diesel and propane.

Propane autogas has emerged a strong player in the Class 1 -7 market, Michael Taylor, Director of Autogas Business Development for the Propane Education and Research Council (PERC), says due to its lower cost of ownership from the vehicles’ initial spec to retirement.

“Seven hundred-plus school districts use more than 12,500 propane powered school buses to transport 700,000 kids to and from school everyday,” he says, “but the fuel is working exceptionally well in fleets of all types.”

Based largely on gasoline-fired engines, propane hasn’t yet found a footing in Class 8. The largest propane engine on the market to-date is the Power Solutions International 8.8 liter, with its 339 hp and 495 lb.-ft. of torque – an engine currently available factory-installed in Freightliner’s S2G.

“The 8.8 liter is probably good for a baby 8,” Taylor says, “but we haven’t really cracked the Class 8 heavy transport market yet. But we do have Class 8 in our sights.”

UPS has almost 1,200 propane-powered package cars as part of its overall investment strategy calling for about 11 percent of all new vehicles purchased to be powered by alternative fuel.