This story has been updated with more developments.

U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-California, said Saturday he and President Joe Biden have reached an agreement in principle to raise the country's debt ceiling and cap government spending. The deal will face its first hurdle in Congress at 3 p.m. Eastern on Tuesday.

That doesn't mean the political theater is over. Republican and Democratic leaders still have to sway enough of their members to vote on the deal in Congress. The agreement must pass before June 5, the day Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen says the U.S. will hit the debt ceiling.

In a statement, Biden says that the agreement is a compromise, which means "not everyone gets what they want. That's the responsibility of governing."

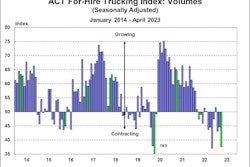

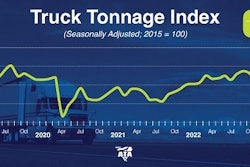

[RELATED: ACT, FTR analysts give glimpse into financial futures]

How did we get here?

The U.S. owes more than $31 trillion. Just like many households have mortgages, car notes and credit cards, the U.S. government also carries debts that allow it to pay for programs and services for Americans.

[RELATED: Is uncertainty the new normal? TPS survey responders are acclimating to market shifts]

The average American turns to banks for borrowing, but the U.S. government sells marketable securities such as Treasury bonds, bills, notes and inflation-protected securities. The $31 trillion is what the federal government owes, with interest, the investors who purchased these securities. It’s akin to using your credit card but not paying it in full every month.

What does the U.S. buy with its credit card? The national debt pays for programs such as Social Security, health care services, national defense, unemployment compensation, food and nutrition assistance, Medicare and more. While the country has carried debt since the Revolutionary War, recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, 2008’s Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic ballooned that debt. In the past 100 years, the federal government’s debt has increased by $408 billion, and counting.

What is the debt ceiling?

The debt ceiling is a self-imposed limit on spending created by Congress. Once the U.S. hits that ceiling, the government cannot increase the amount of outstanding debt, meaning it will lose the ability to pay its bills, its employees and contractors, and fund programs and services that depend on debt spending.

The U.S. has never defaulted on its debts, and the White House insists it never will.

“America is not a deadbeat nation,” Jean-Pierre said Wednesday. “We pay our bills. We have never defaulted in our history, and we never will.”

It is estimated the U.S. will hit its debt ceiling on June 1. Taking on new debt over the ceiling will require an act of Congress, which has led to the negotiations between President Joe Biden and House Speaker McCarthy.

Jim Meil, ACT Research’s principal, industry analysis, says, at the risk of oversimplification, Biden’s position is government spending on programs was approved by Congress and constraining expenditures on these programs is hypocritical and exposes the American — and global — economy to unnecessary risk. The White House is pushing for higher taxes on corporations and the highest individual earners if cuts to approved budget items are to be considered.

On the other hand, Speaker McCarthy and Congressional Republicans say the national debt is unsustainable. It’s best, they counter, to deal with the problem now rather than kicking the can down the road to become an even bigger number (and problem) later. Republicans say the November 2022 elections gave them a mandate to reverse expansionary federal spending.

“My guess is this is all resolved before the deadline,” MacKay & Company Senior Market Analyst and Client Consultant Dave Kalvelage says. “A lot of political theater is happening right now.”

What would happen if the U.S. defaults?

Well, because it’s never happened, no one knows.

Meil says one thing that could happen is the Treasury would give priority to debt payments, pushing down all other commitments. This is the equivalent of not paying some of your bills to pay the house note.

“This would limit damage to financial markets, but open the door to economic dislocation, political recrimination, and considerable litigation, with severe impacts to the economy,” he says.

Another option the Treasury has is to stop all payments, both programmatic and on debt. “That could be catastrophic,” Meil says, as it would threaten the integrity of those bonds, notes and securities the Treasury uses to borrow money. They are, for better or for worse, the bedrock of the global financial system, Meil says. Stopping payments would spike interest rates, tank the stock market and could interrupt the entire global financial system.

The severity of the tremors to the system would depend on how long either solution would last.

“The longer the impasse, the deeper the downside,” Meil says.

What about heavy-duty trucking, specifically?

Just like no one knows what would happen to the broader system, it’s also nearly impossible to predict the effect on the trucking industry. Meil says even a last-minute deal would mean little to no impact, but a default, even a short-term one, would have harmful effects.

“It would likely push the economy and transportation markets into a real recession (not a maybe recession like we have now) and would hurt the ability of trucking businesses to borrow money,” Meil says. “And no doubt, it would bring about higher interest rates. In this scenario, cash will be preserved wherever possible, leading to an acute decline in spending and an economic recession.”

[RELATED: Bob Dieli says the economy is entering a two-front war]

Of course, the longer any shut down is, the more effects there will be. Kalvelage predicts little impact to the heavy-duty aftermarket or the economy if a shutdown lasts a week. But beyond that, all bets are off.

“The effects quickly start to snowball,” Kalvelage says. “Suspension of federal payments to government employees and government programs would impact people’s lives (missed payments for cars, credit cards or other spending) and ripple through the economy quickly.”

It's too late to come up with a response plan if your business doesn’t already have one, Meil says, but there are things you can do. Check your contingency plans regarding supply chain management, personnel and financial management. And get your team together to talk about some of those lessons you learned in March 2020 when COVID-19 broke out.