No state has pushed the auto and trucking industry harder toward the adoption of electric vehicles than California, but as the state lately found itself in the grips of a blazing summer heatwave, its maxed-out power grid may have dealt a shock to the trucking industry in its march toward electricity as a primary fuel.

California Governor Gavin Newsom's office issued Sept. 6 a "flex alert" warning from the state's power producers urging residents "to reduce their electricity consumption between 4 p.m. and 9 p.m." to save power and reduce the risk of outages.

"Avoid using large appliances," the state told residents, including trucking companies it's pushed toward electric vehicles with big incentives/subsidies. The full text of the flex alerts found on the website of the California Independent System Operator, which includes most of the state's power producers, also said to avoid charging electric vehicles during these times.

The flex alert was continued until Sept. 9 and expanded to 3 p.m. to 10 p.m.

If power producers can't keep up in a heat wave, how could they accommodate hundreds of thousands of electric trucks demanding megawatts of power once or more a day? Not only does this pose a question for electric trucking, but everyday life as well, as California moves to phase out gas stoves and gas-powered small engines.

California answers the tough questions on electric vehicles

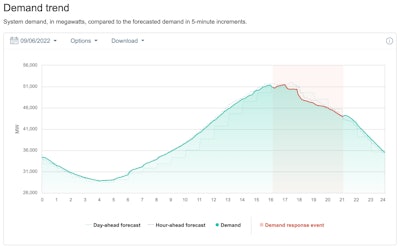

A graph from California ISO shows a sharp reduction in power use around the time Newsom announced the flex alert.California ISO

A graph from California ISO shows a sharp reduction in power use around the time Newsom announced the flex alert.California ISO

Governor Newsom took no shortage of heat for the flex alert declarations from his political opponents, but perhaps the only thing more shocking than the declaration itself is that it worked. Within five minutes of Newsom's office tweeting, power usage fell off a cliff and remained at workable levels. The feared blackouts never came.

But what would happen if the state succeeds in transitioning diesel fleets to electric fleets? After all, the state is set to ban as many as 76,000 trucks with a pre-2010 emissions-spec engine from operating in the state by 2023. Meanwhile, California's also offering up to $120,000 in incentives for trucks like Freightliner's Battery Electric eCascadia.

Chris Shimoda, the California Trucking Association's senior vice president of government affairs, said the state "has a huge task on its hands to accommodate its electrification goals," and pointed to the recent flex alerts and the decision to extend the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant's service life as evidence that "we are already behind the eight ball in preparing the grid."

Shimoda, like many industry experts, stressed that right now, battery electric trucks only make sense for smaller vehicles and lighter duty cycles, and that the charging infrastructure "is nearly non-existent. ... CARB’s own estimates say we need to be putting in more than 300 chargers a week between now and 2035 to support their proposed regulation, including nearly 10MW of public charging each week," or about one or two major retail locations.

"California’s grid cannot accommodate truck charging without upgrades," which could take anywhere from 1.5 to 10 years, Shimoda said.

PG&E, California's largest power provider, responded to the flex alerts by saying the utility "always encourages EV drivers to take service on time-of-use rates, which provide a price signal encouraging drivers to charge overnight when energy tends to be inexpensive, or in the middle of the day when low-cost renewable energy is plentiful." These time-of-use rates mean that electricity in California costs different late at night and in the early morning than in the afternoon hours of peak demand. Port of Oakland small feet owner Bill Aboudi, who runs two electric yard hustlers and has applied for grants to buy more EVs, says it comes out to something like 32 cents per kilowatt hour during peak hours, but drops down to about 12 cents per kWh at night. Overall, he said, his small EV application can comfortably charge during off-peak hours, as the trucks just roll trailers around on flat land with no inclines.

Colin Murphy, the deputy director of the UC Davis Policy Institute for Energy, Environment and the Economy, said that Aboudi's experience would match with the wide majority of fleets transitioning to EVs, and that if your utility provider doesn't already have you on a time-of-use plan, "they probably will in five or ten years."

Murphy urged some perspective around the flex alerts and California's ailing grid, saying these few days during an intense heatwave represented the "five or six worst hours of the year" for power demand, and that most of the time -- and in the wide majority of use cases -- charging electric vehicles, passenger or commercial, shouldn't overtax infrastructure.

[Related: Cummins, other hydrogen ICE proponents hoping for zero-emission status in California]

Think of drayage, school buses, garbage trucks, beverage hauling: all of these industries could switch to EVs with relative ease and charge comfortably during off-peak hours.

Between EVs that come programed with a smart timer for charging and "half a dozen different tech options," both onboard the vehicles and off the shelf, Murphy said there are plenty of options for keeping electric vehicles topped up off-peak. Many passenger electric vehicles can already wait until off-peak hours to charge, and "most people don't drive more than 40 or 50 miles a day," while passenger EV batteries can comfortably run 200 to 300 miles a day, said Murphy.

But Murphy admitted that in the wide world of trucking, there will likely be some use cases when an EV absolutely does need to be charged during peak hours, and even during a heatwave. What to do in those cases? Go ahead and plug it in. The flex alerts California has seen are requests by the grid operator to reduce consumption where possible, not law. Murphy estimated that even with large-scale adoption of electric vehicles, electric appliances and electric yard equipment, these devices still wouldn't move the needle that much in terms of overall power consumption for at least a decade. Elsewhere, experts have estimated that California may need to increase energy production as much as 50% to meet the future needs, but Murphy said that change is coming thanks in part to funding from the Inflation Reduction Act and investments California has made in its grid over the last decades.

Importantly, "the load growth we're forecasting is partially offset by the fact that existing uses of electricity were consuming less because of these efficiency investments, so not all of the additional load has to be matched with new supply," he said. "Most of the modeling, for California at least, indicates that the total demand on the grid is totally manageable with expected levels of supply growth, even if we stop building new fossil fuel power plants."

On that point, Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) -- the largest utility provider in the U.S. -- agrees, and it encouraged fleets to take advantage of its EV Fleet program, which "builds the electrical infrastructure for customers’ medium- to heavy-duty EVs from the utility pole (electric service) to the customer meter, or to the charger depending on which ownership option the customer choses."

The utility encouraged fleets looking into electrification to get in touch before building. This wisdom extends beyond California as well. At the CCJ Symposium in August 2021, Cedric Daniels, the electric transportation manager at the Alabama Power Company, said the major successes he's seen in fleet EV infrastructure have come from "those times when folks engage as many people as possible in what they might consider."