Editor’s note: This is part of the third article in a three-month series examining the driver shortage, measuring its impact on trucking operations and exploring methods to mitigate the crisis.

Last September, Starsky Robotics completed the longest end-to-end autonomous trip on record, hauling Hurricane Irma recovery aid 68 miles through Florida with a person in the cab but without their intervention.

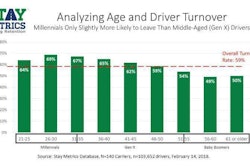

Last September, Starsky Robotics completed the longest end-to-end autonomous trip on record, hauling Hurricane Irma recovery aid 68 miles through Florida with a person in the cab but without their intervention.With driver turnover rates bumping 90 percent last year, shippers could find only one available truck for every 12 outbound loads — the lowest ratio in 13 years, according to DAT Solutions.

As carriers fight for enough humans to keep trucks moving, the evolution of automation has put truck driving in an interesting place. How much longer will a human driver be necessary?

Earlier this year, San Francisco-based technology company Starsky Robotics completed a seven-mile drive in Florida without a person in the cab. The truck’s flesh-and-blood driver was stationed some 100 miles away and monitored the tractor through a network of cameras and sensors.

The goal of Starsky’s platform, where a human remotely drives the truck only on and off the highway before ceding control at highway speeds, is to ease the industry’s driver shortage.

“We can provide more safety features and even comfort features or assist features, which would make the experience better for the driver and, in some cases, less fatiguing or easier than it may be now. All those things make it a more accepting environment for younger people.”

— Jon Morrison, Wabco’s president of the Americas

The remote driver “should be monitoring the truck at the beginning and end of the trip,” says Stefan Seltz-Axmacher, the company’s co-founder. Once the truck is in full autonomous mode, “the guy in the office should be paying attention to a number of other trucks.”

But there are roadblocks. Taking the driver out of the vehicle and operating on a public road is legal in only a handful of states, and driving beyond hours-of-service allowances is legal in zero states. But Fred Andersky, director of marketing and government affairs for Bendix, says with some regulatory cooperation, truck automation could extend a driver’s workday by allowing him to take mandated breaks while the truck is moving. That may not bring more drivers into the field, but it will allow existing drivers to move more tonnage, he says.

“We could be at a point where the technology would let the driver take his eight- or 10-hour rest break, but the truck is able to continue on its route,” Andersky says. “Those types of things actually enable us to squeeze more out of existing driver time without unduly burdening the driver while, in fact, making the driver even more efficient.” If driver assist technologies enable a driver “to do other things in his day that extend his day, and we have regulations that allow it, then automated systems can help reduce a driver shortage.”

Jon Morrison, Wabco’s president of the Americas, says absent such regulatory change, fleets can adopt autonomous technologies to gain an edge in recruiting a generation of new drivers accustomed to relying on electronic support across many aspects of their lives.

“We can provide more safety features and even comfort features or assist features, which would make the experience better for the driver and, in some cases, less fatiguing or easier than it may be now,” Morrison says. “All those things make it a more accepting environment for younger people.”

Regardless of how autonomous technologies are implemented or how future regulatory changes cooperate, experts agree that drivers – in some capacity – will remain an important part of freight movement for a long time.

“When you look at the overall amount of freight flowing, there’s a lot of freight that flows on a shorter-haul – and that’s getting shorter – and a more regional basis,” making full autonomy challenging, Morrison says. “I think scale is really the question. I think you’ll see some deployment in specific use cases that are less complicated or less restricted.”