The math is bothering me on merging railroads. Stick with me for a moment.

If Railroad A has 100 miles of track capacity, and Railroad B has 100 miles of track capacity, then combined, the two have a total of 200 miles of track. So, if the two railroads merge, into Company AB, they still have just 200 miles of track. Right?

One of the headlines recently spread across multiple sources stated that that the proposed UP-NS rail merger had targeted capturing new market share of “2 million truckloads annually.”

I began wondering about where the extra capacity was supposed to come from.

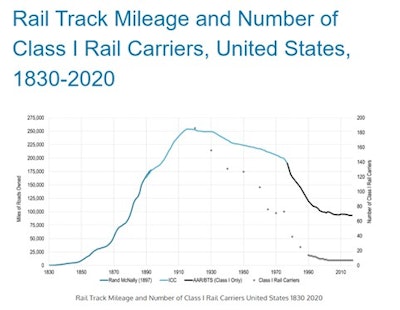

Let’s look at the historical investment in adding capacity. I updated my research from a few years ago in NACFE’s report Intermodal & Drayage: An Opportunity to Reduce Freight Emissions. Looking at the latest tabulations of Class 1 rail trackage in the U.S. Several different sources agreed that Class 1 rail trackage is currently somewhere around 95,000 miles. This peaked over a century ago and has been on the downhill part of the rollercoaster since. A great graph dating back to the start of railroads in 1830 was compiled by Jean-Paul Rodrigue in his 2024 The Geography of Transport Systems.

Several of the rail industry sources document the amazing amount of capital and expense the Class 1 railroads spend on maintenance each year. It is a distinguishing feature of railroads in that they pay for their own maintenance, that, according to the American Association of Railroads (AAR), amounts to $23 billion annually. But digging a bit deeper, that amount is truly mostly maintenance, not new trackage, which is a number that various AI search engines estimated at between 100 and 2000 miles of new track per year, mostly in rail yards. That investment increases as inflationary factors — such as labor costs, steel costs and other materials — hit, as well as the need to add new safety equipment and replace aging hardware.

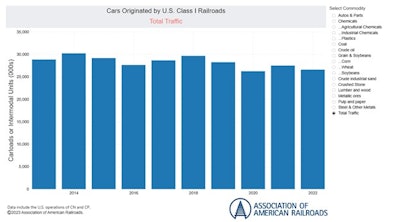

Another way to look at adding capacity might be to look at rail traffic over the last several years. The AAR shows that total carloads and intermodal units over the last decade has been decreasing slightly.

If net trackage is not changing appreciably each year, and net carloads are similarly not increasing, then where is the added capacity supposed to come from to wrest freight away from trucking?

A contrary headline came out recently from various sources such as CCJ, Barrons and others, that the purpose of the rail merger is to position the rail industry to better combat market loss expected by railroads because of the introduction of autonomous trucks.

So, which is it, railroad expansion or entrenchment? Perhaps it’s both.

But the math still bothers me having ridden trains and followed rail most of my life since stepping on board the 1976 Bicentennial American Freedom Train as a kid. Railroads are capacity limited by trackage. If you’ve ridden Amtrak, you can experience in many places how little parallel trackage there is, which creates bottlenecks where trains have to be shunted into sidings to let other trains pass. During really good rail freight times, major east-west corridors from California ports are operating at near track capacity, with 200 car rail “consists” — the industry phrase describing assembled trains — spaced just 10 to 20 minutes apart.

It begs the question if Company A and Company B combine their tracks, where do they add capacity?

Somehow streamlining handoffs between two railroads will make more room on the tracks?

And doesn’t moving freight by rail inherently mean adding trucks at both ends of the rail line to distribute that freight beyond the 95,000 miles of Class 1 rail lines? Won’t that double the number of trucks needed to move the freight the final mile?

Another argument the rail industry makes is based on lower emissions from railroads versus trucks. That argument is getting less viable as new 2025 and later model year trucks are starting to exceed 12 MPG, and battery electric ones are exceeding 18 MPGde versus the 5 to 6 MPG used in older comparisons. But forget those details, in 2026 with the federal government largely abandoning caring about CO2 emissions in regulations, doesn’t the comparison really hinge on traditional factors like speed of delivery, reliability and cost? Shouldn’t the railroads be figuring out how to beat trucks on those major factors?

If railroads are truly interested in becoming better performers, perhaps they should focus on working better with the trucking industry rather than fighting it, taking a transportation system perspective where rail and trucks work together in a system to move freight faster, cheaper and more reliably.