Manufacturers say automatic transmissions make drivers safer and more productive. Older drivers say they’re a crutch. Who’s right?

Manufacturers say automatic transmissions make drivers safer and more productive. Older drivers say they’re a crutch. Who’s right?Adapting automatic transmissions for use in trucking has proven to be difficult. One reason was the inability of mechanical engines and transmissions to “talk” to one another and ensure optimal performance across applications and road conditions.

More on automatic transmissions: Will drivers come around?

Early transmissions had a hard time figuring out what drivers wanted. Complaints concerning both frequent and uneven shifts were common, as were problems with “searching” – when transmissions would struggle in hilly terrain to find and stick with an optimal gear. Other problems along those lines emerged at low speeds – in traffic and while docking.

Eaton’s UltraShift Plus automated manual transmission is a computer-controlled manual gearbox that features a dry clutch but only two pedals to excel in long-haul trucking applications.

Eaton’s UltraShift Plus automated manual transmission is a computer-controlled manual gearbox that features a dry clutch but only two pedals to excel in long-haul trucking applications.Even so, AMTs continued to make inroads in trucking. Now, engines and transmissions are sharing more data, so performance issues are getting smoothed out. AMTs now are being spec’d on a significant share of new trucks for reasons including fuel economy and easier driver training. The trend is likely to continue.

Two types of automatic transmissions are available for heavy-duty trucks: Automated manual transmissions and automatic transmissions. Both are two-pedal designs. Most drivers probably would be hard-pressed to tell much of a difference between them in real-world driving situations.

The basic difference is that automated manuals are manual gearboxes, with all the clutch actuation and gearshifts handled by electronically controlled systems. A true automatic transmission “for a Class 8 truck is usually fully automatic, like a typical car transmission, with planetary gearing with several multi-disc packs for clutches,” says Ed Saxman, product marketing manager with Volvo Trucks North America. These transmissions have a torque converter to enable powershifts of the planetary epicyclic gearing units that provide the various gear ratios.

An automated manual transmission uses the gearbox of a manual transmission and shifts it by computer, using a computer-operated single large-diameter disc clutch, otherwise similar to a manual clutch.

Allison’s automatic transmission features fluid drive and a torque converter. Adherents argue these provide 100 percent power and double rim pull, making them ideal for vocational applications.

Allison’s automatic transmission features fluid drive and a torque converter. Adherents argue these provide 100 percent power and double rim pull, making them ideal for vocational applications.Allison Transmission’s automatic is designed with the company’s Continuous Power Technology, meaning it never interrupts torque and power to the wheels, says Steve Spurlin, executive director of international application engineering and vehicle integration. “It also uses a torque converter as the starting device,” he says.

An automated manual has incorporated electronic controls with basic manual transmission architecture to facilitate automated shifting of the gears and the input clutch-starting device. Both the automated manual and the basic manual interrupt power and torque every time a shift is made, whether automated or manually, Spurlin says.

According to Steve Rutherford, powertrain marketing manager for Caterpillar OEM Solutions Group, the advantages of a pure automatic design are a perfect fit for the company’s vocational truck line. He adds that both transmissions work well in specific applications.

“Both types of transmissions have two pedals and a shift pad instead of a gearshift lever,” Rutherford says. “It took a lot of work to perfect automated manuals to engage a dry clutch and generate well-synchronized shifts. What they’ve done with those products is amazing.”

Mack Trucks says the take rate for its mDrive AMT is currently in the neighborhood of 38 percent, which aligns with other OEMs that report figures ranging from 35 percent to the low 40-percent range.

Mack Trucks says the take rate for its mDrive AMT is currently in the neighborhood of 38 percent, which aligns with other OEMs that report figures ranging from 35 percent to the low 40-percent range.But many drivers – primarily older ones – feel that automatic transmissions somehow detract from a skill set they’ve honed over decades. “I’m a truck driver, not a steering wheel holder,” says Carl Ciprian, a driver with Fayette, Ala.-based N&N Transport. Ciprian never has driven an AMT and says he never will, preferring to stick with an Eaton-Fuller 18-speed manual gearbox.

“I can understand why fleets like AMTs,” he says. “It’s all about fuel economy. You know – ‘Instead of teaching new drivers how to drive, just give them all an automatic transmission, and turn them loose on the highway.’ ”

Ciprian, however, sees truck driving as a skill – one in which a truck driver needs to be engaged to do it properly. “Changing gears, and having the additional control over the vehicle that a manual transmission gives you, is an integral part of that,” he says.

But fleets are gravitating toward automatic transmissions – and in surprisingly high numbers. David McKenna, director of powertrain sales for Mack Trucks, says the mDrive is being spec’ed in about 38 percent of Pinnacle tractors, similar to the 35 percent to low 40 percent range that other manufacturers report. Saxman says that more than 50 percent of all new Volvos sold this year have been spec’d with the company’s I-Shift AMT.

Several OEMs – including Detroit with its new DT12 – have developed integrated powertrains that share proprietary information between the engine and transmission to deliver optimal fuel economy consistently.

Several OEMs – including Detroit with its new DT12 – have developed integrated powertrains that share proprietary information between the engine and transmission to deliver optimal fuel economy consistently.There are several reasons for this significant shift, experts say. Shane Groner, Eaton’s manager of NAFTA product development, says his company’s UltraShift Plus AMT now is enjoying a 25 percent spec rate in heavy-duty trucking applications, with on-highway applications logging in at about 15 percent.

“There are still a lot of highly experienced drivers out there who can get the most out of a manual transmission,” Groner says. “Those gearboxes are essentially bulletproof. If you’re a fleet and you’re blessed with an abundance of experienced drivers, and upfront costs are still your primary expense driver, then it’s hard to argue with manual transmissions.”

On the other hand, Groner says, driver skill sets in the industry are changing rapidly. “Many young drivers have never driven even a car with a manual transmission, so they lack even basic familiarity with them,” he says. “The driver demographic is changing. Older drivers are retiring, and they are not being replaced.”

For fleets, though, the appeal of automatics goes far beyond driver preferences, with safety and fuel economy topping the list.

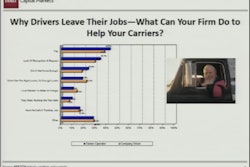

“We’ve found that automatics help with driver recruitment and retention,” Spurlin adds. “Automatics allow less-skilled drivers to be very productive. They are also a large help with safety because the drivers can stay focused on the road or the task at hand instead of shifting gears.” Also, drivers do not get as fatigued with an automatic since they do not have to shift constantly.

“We have encountered many ‘converts’ – veteran drivers who were once skeptical but now prefer our I-Shift automated manual transmission,” Saxman adds. “Manual transmissions are difficult to ‘skip,’ and most drivers use all 10 gears.”

In contrast, Saxman says, AMTs like the Volvo I-Shift can reach top gear by using just six of 12 available forward ratios. “Fewer interruptions mean faster acceleration,” he says. “As far as fuel efficiency, it is often said that an automated transmission can make the worst driver deliver the same fuel mileage as the best driver, because it’s in the right gear at the right time – all of the time.”

The way fleets spec a drivetrain is changing, and automatic transmissions are a key part of that formula, says Brad Williamson, powertrain marketing manager for Daimler Trucks North America. “The industry at large is now spec’ing lower gear ratios, with direct-drive powertrains becoming more common,” he says.

The concept of “downspeeding” – operating a diesel at lower rpms while at cruise speeds – is being driven by the push for better fuel economy, Williamson says.

“Information is key,” he says. “If you designed both the engine and the transmission, then they can ‘talk’ to one another and share critical information, like what the driver wants, the fuel map, the load, the grade and what the engine is trying to do. The transmission can manage all this information and deliver the best performance possible given all those criteria. A driver just can’t do that consistently. Even if they had all that information, they couldn’t process it and manage the shifts to deliver the same level of performance an automatic transmission can.”

Williamson’s point addresses the latest development in the evolution of automatics in heavy-duty trucking: complete powertrain integration. To date, Volvo, Mack, Daimler and Eaton – via a just-announced partnership with Cummins – all have developed highly integrated powertrains that share unprecedented levels of proprietary information between the engine and transmission to deliver consistently optimal fuel economy at all times.

“It all boils down to the electronics,” McKenna says. “When you have Vendor A supplying an engine and Vendor B supplying a transmission, rarely do those two components share 100 percent of their information 100 percent of the time. Typically, the transmission in those instances ends up making decisions with about 75 percent of the data it needs to make an optimal shift.”